No

Atlantic Canada

The first part of North America to be discovered by Europeans, Canada’s four Atlantic provinces comprise a small group of islands and peninsulas on Canada’s eastern coast. Though low in population and economically weak, they possess a proud, centuries-old culture that combines a distinct mix of British, Scottish, Gaelic and French customs, creating a unique, tradition-oriented people. Almost everyone in Canada claims to find Atlantic Canada quaint and interesting — even if few are exactly scrambling to live there.

Note: In most parts of Canada, it’s common to use the term “Maritime provinces” or “the Maritimes” to refer to the provinces of Atlantic Canada. Within Atlantic Canada itself, however, the term “Maritime” is understood to exclude the province of Newfoundland, which has a somewhat different culture and identity from the rest of the Atlantic provinces, as we shall see.

Sunset at Peggy Cove, Nova Scotia.

Jay Yuan/Shutterstock

Geography of Atlantic Canada

Atlantic Canada comprises a small collection of islands and peninsulas attached to the coast of eastern Quebec and extending into — you guessed it — the Atlantic Ocean. Together, they form a crude crescent-shaped bay known as the Gulf of St. Lawrence that connects the Atlantic Ocean to Quebec’s St. Lawrence canal, which serves as Canada’s busiest eastern trading port.

The Atlantic Canadian landscape is one of Canada’s most recognizable, with pine forests, hills and dangerous rocky cliffs that have spawned — out of safety concerns — an iconic lighthouse industry. Since the region is surrounded by water, coastal areas can be particularly cool, wet and foggy with cold, stormy winters (raincoats are another proud Maritime icon) and mild, pleasant summers. Interior, or inland regions, by contrast, tend to be considerably drier, and in winter months receive some of the largest snowfalls in Canada.

In contrast to the other provinces, the four Atlantic Canadian provinces are all quite small with sparse populations. Most can be driven across in only a couple hours.

History of Atlantic Canada

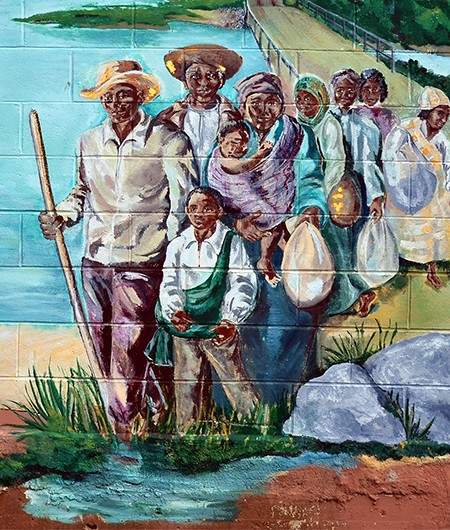

Like much of eastern Canada, the Maritimes originally belonged to the French. Established in 1604, the royal French colony of Acadia encompassed all the modern-day Atlantic provinces, and was one of the Empire’s most strategically useful outposts as the gateway to North America. Of this fact nearby British settlers were extremely jealous, and the two powers fought back-and-forth wars over the colonies for most of the 17th century, with the Brits finally securing control of most of the area in 1714, following the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). Having acquired the region, Britain proceeded to deport all French colonists — also known as Acadians — in what is still remembered as one of the most shameful episodes of Canadian history. Though some Acadians would later migrate back, a lot of the deported wound up in Louisiana, and helped form that state’s unique culture. The lovable term “Cajun” is descended from “Acadian,” in fact.

Cleared of the French, the Acadian colonies remained mostly vacant until the aftermath of the American Revolution (1775-1783) sent a vast migration of pro-British Loyalist refugees northward, who turned the region into a thriving community of English loggers, fishermen and shipbuilders. By this point, the British colonial bureaucrats had divided and renamed the territory into the four regions we know today: Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. By the mid-19th century, all four colonies had won a high degree of self-government, but were also economically stagnant. The idea of forming a larger, self-governing colonial federation with Ontario and Quebec as a path to greater prosperity was proposed, and Nova Scotia and New Brunswick formed two of Canada’s first four provinces in 1867. Bankrupt PEI jointed in 1871, but Newfoundland refused, and remained an independent, self-governing British colony until 1949.

Throughout the 20th century, all of the Atlantic provinces struggled with serious economic problems and remain the poorest regions of Canada to this day. The “root cause” of Maritime poverty is obviously quite a controversial and much-debated topic, but an undeniably factor has been the decline of many of their traditional industries, such as fishing, forestry and shipbuilding.

The Tall Ships Nova Scotia festival in Halifax.

Matthew Jacques/Shutterstock

Nova Scotia

A large peninsula shaped like the lobster claws it’s famous for, Nova Scotia is the biggest and wealthiest of the four Maritime provinces. Home to Halifax Harbour, Canada’s main Atlantic port, Nova Scotia was originally known as a hub for shipbuilding and naval bases, as well as a welcoming point for many European immigrants, embodied by its famous Pier 21 — Canada’s answer to Ellis Island. In the 20th century, the provincial economy was tied to two notoriously unsustainable natural resource industries — coal and fishing — and by the 1990s both had collapsed. Today most residents work in tourism or the service sector.

Over 70 per cent of Nova Scotians live in coastal communities with half of the provincial population located in two large cities: Halifax, which is on the main peninsula, and Sydney, on Cape Breton Island to the north. Nova Scotia’s geography is generally sloping, with the eastern half of the province dominated by hills and forest-covered mountains, while the western half houses flat plains and farmland. The provincial coast features rocky beaches covered with massive grey stones, washed smooth after thousands of years of lapping waves.

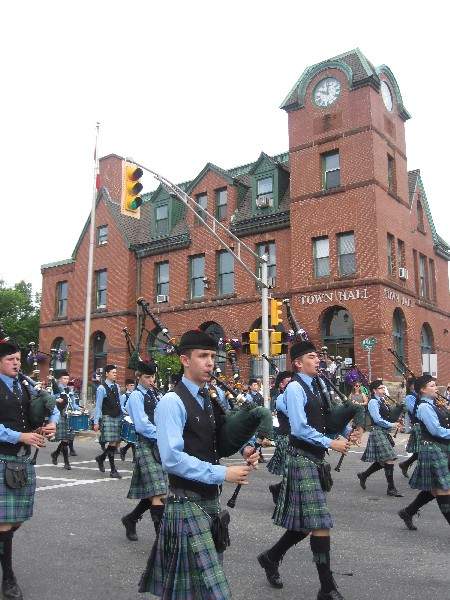

Latin for “New Scotland,” Nova Scotia has been the historic home of a colourful Maritime culture spread by immigrants from England, Scotland and Ireland. Well into the 20th century, it was not uncommon to come across rural Nova Scotian families who spoke Gaelic as their first language, and musicians like Ashley MacIsaac (b. 1975) and Natalie MacMaster (b. 1972) have kept a distinctive Celtic tradition of aggressive fiddle-playing alive and popular.

The Hopewell Rocks in the Bay of Fundy.

Vincent St. Thomas/Shutterstock

New Brunswick

New Brunswick is a square, mountainous province best-known for its southern coast, the Bay of Fundy, which is home to the highest tides in the world, iconic “flowerpot rocks,” and thriving communities of humpback whales and dolphins. Most New Brunswickers live in the cities of Saint John (not to be confused with Saint John’s, which is in Newfoundland) and Moncton. The provincial capital of Fredericton, unusually, sits a somewhat distant third.

Unlike their compatriots in the other Maritime regions, many New Brunswick Acadians (French-Canadians) were allowed to return to their province following Britain’s mass deportation of French settlers in the 1750s, and to this day, northern New Brunswick retains a significant population of French-speakers. In 1969 New Brunswick declared itself Canada’s first officially bilingual province, and it’s estimated more than 30 per cent of New Brunswickers speak French as their first language — the largest percentage outside of Quebec.

With upwards of 85 per cent of the province covered by forest, logging and shipbuilding have been the traditional backbone of the New Brunswick economy, though both have steadily declined in recent decades. Today, the New Brunswick economy is known for being significantly dominated by the family-run J.D. Irving corporation, which has come to control a vast array of industries, including lumber mills, gas stations, convenience stores, newspapers, and TV stations.

Prince Edward Island

A small crescent-shaped island located in the gulf between New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, PEI (as it’s known) occupies a mere 5,700 square kilometers of land and contains only 140,000 people making it by far Canada’s smallest province. It has long struggled to achieve national attention as a result, beyond jokes about its size.

PEI was originally little more than a floating plantation owned by absentee British landlords, who drove property values up so high no one could afford to live there. This single issue dominated the island’s early history, with the colony first refusing (1867) and then agreeing (1873) to join Canada in an effort to get Britain to solve the problem. The population continued to remain low into the 20th century due to a general lack of industry beyond potato farming and fishing.

Due to its small size, virtually all of Prince Edward Island is developed and inhabited, with about a quarter of all residents living in the capital city of Charlottetown and the rest scattered about in small villages across the island. Sprawling green plains, red sandstone cliffs, deciduous forests, and old-fashioned clapboard houses have helped turn the province into a tourist mecca for those seeking quaint Atlantic charm — which has, in turn, helped keep the provincial economy afloat.

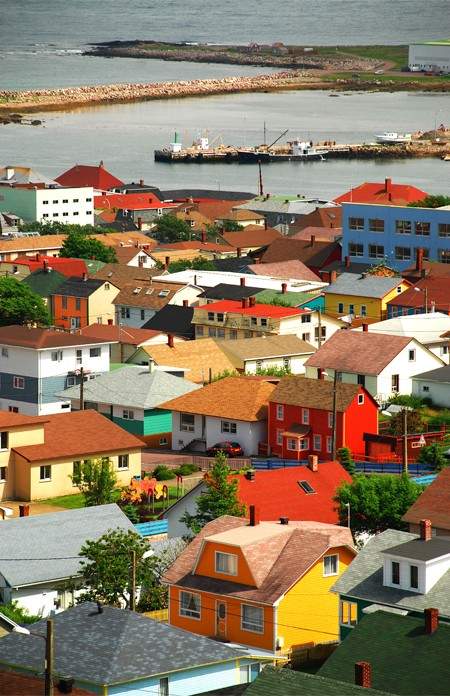

Colourful houses in St. John's.

Elena Elisseeva/Shutterstock

Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland traces its founding all the way back to 1583, when the British explorer Sir Humphrey Gilbert (1537-1583) claimed the rocky island as Britain’s first overseas colony. The British proceeded to go to great lengths to prevent people from actually living there, preferring to use the colony as a powerful naval base through which they could control much of the lucrative American fishing industry. Only in the 19th century did full-scale settlement begin, and as the colony’s population of British settlers steadily grew, Newfoundland gradually gained political independence from Britain much the same way Canada itself did. Consistently refusing to join Canada, Newfoundland spent the years from 1855 to 1934 as a self-governing dominion of Great Britain, with its own prime ministers, national anthem, flag, Olympic team, and the rest.

Hit particularly hard by the Great Depression (1929-1933), Newfoundland gave up its independence in 1934 and agreed to once again be directly administered by the British for 15 years, before finally voting to join Canada in 1949. In the postwar era, a depletion of fish stocks and a failure to develop other industries doomed the new province to a seemingly perpetual state of recession, with high unemployment, poverty and welfare dependency. Only in recent years, with the discovery of oil off the provincial coast, has Newfoundland finally begun to escape from its long shadow of economic dysfunction.

Despite having recently celebrated their 60th anniversary as a province of Canada, Newfoundlanders (or “Newfies” as they are affectionately, or sometimes insultingly, known) still retain a number of unique cultural traditions from their long history of independence. They speak with different accents, use different slang, celebrate different holidays and eat many different foods than other Canadians, and retain a population that has far fewer immigrants and minorities than the rest of the country. Despite controversial government efforts to promote city living, the province’s small population remains scattered around the island, with a very small minority of residents living in Labrador, a resource-rich chunk of northern Quebec that Newfoundland has long fought to keep under its control.