No

Canadian Foreign Policy

In general, Canadian foreign policy has operated largely in sync with that of America and Europe, with the Canadian government acting as a loyal partner in the dominant western alliances of the day. This has included participating on the allied side of both world wars, actively participating in the United Nations and NATO, defending democratic-capitalist causes during the Cold War, and making military, diplomatic, and financial commitments to help promote global stability and justice in the modern era of terrorism and rogue states.

At the same time, Canadian foreign policy-makers have long championed the idea that Canada should always behave cautiously and pragmatically in its deeds and rhetoric, and shy away from overly divisive or belligerent actions that could compromise the country’s reputation as a calm, conciliatory, friendly nation, or threaten the wealth and stability of its economy. The central challenge of Canadian foreign policy has been trying to square the Canadian public’s strong commitment to abstract principles like democracy, freedom, and the rule of law with the country’s practical desire to protect its interests, image, and safety.

Themes of Canadian Foreign Policy

Independence

Canada remained a colony of the British Empire until 1931, meaning there was no such thing as “Canadian foreign policy” before then, as Britain did not permit its colonies to sign treaties, form alliances, appoint ambassadors, go to war, or pretty much interact in any substantial way with the wider world without London’s approval. Canada did participate in a few overseas adventures in the early 20th century, fighting in the Boer War (1899-1902) against Dutch rebels in British-run South Africa and in World War I (1914-1918) defending Britain’s allies from the armies of Imperial Germany, but this involvement was largely automatic, given all British colonies were expected to fight for British interests. In 1931, the U.K. passed the Statute of Westminster giving its self-governing white colonies the right to make their own foreign policy choices. Canadian politicians have taken Canada’s right to make independent decisions of war and peace very seriously ever since, not only in regards to Britain, but other friendly nations as well.

Canada eagerly fought alongside its allies in both World War II (1939-1945) and the Korean War (1950-1953), but as the Cold War (1945-1990) continued to unfold, Canada began to chart an increasingly independent course. When Britain, France, and Israel invaded Egypt during the Suez Crisis of 1956, Canada remained neutral. After the Cuban Revolution of 1959, Canada maintained economic and diplomatic ties to the government of Fidel Castro (1926-2016), defying U.S. and South American efforts to isolate the Marxist regime. When war between communist and non-communist forces in Vietnam broke out in the mid-1960s, Canada similarly resisted calls from America and Australia to intervene militarily to help the non-communist side. More recently, Canada was one of several western nations to oppose the Iraq War (2003-2011) against Saddam Hussein (1937-2006) led by Britain and the United States.

When Canada breaks from its traditional allies the reason is usually a disagreement about strategy, not goals. Canada favored the anti-communist side in Vietnam, for instance, and opposition to the war did not prevent the country from providing military and economic assistance to the United States during the conflict, just as opposition to the Iraq war would not prevent Canada from doing the same some 40 years later. Canadian demonstrations of foreign policy independence are just that: high-profile actions designed to demonstrate that Canada is not an automatic ally of any partner or cause, but rather a fully independent nation capable of making decisions for itself.

Prime Minister Trudeau with the leaders of other western nations at the 2018 G7 summit in Charlevoix, Quebec.

Canada’s Global Alliances

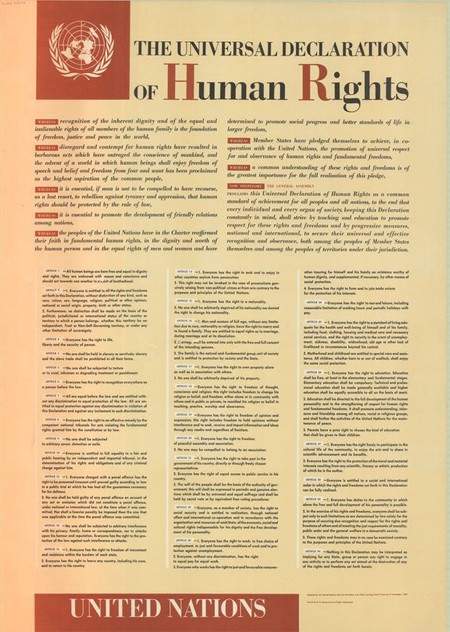

Canada’s willingness to take occasional contrarian positions should not disguise the fact that the country takes the idea of stable, global alliances between like-minded countries very seriously. Canadians are often taught, in fact, that their country’s “good global citizenship,” and active participation in every major international organization forms one of Canada’s most respectable qualities in the eyes of foreigners.

Following the end of World War II, Canadian politicians and diplomats were leading figures in the postwar efforts to help try and permanently re-order global affairs under a more stable regime of international law and regulation. Canada was a founding member of the United Nations, and many other important international organizations set up for this purpose, including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, see sidebar), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Trade Organization (WTO), and World Bank, which aimed to stabilize the global economy.

Canada’s strongest international ties continue to be with the United States and the United Kingdom, though the Canadian relationship with France, Australia, and Israel is exceptionally close as well. For historical, ideological, cultural, and strategic reasons, these are the countries to which Canada and Canadians maintains the deepest bonds, and any disputes or disagreements between them are bound to provoke headlines.

Leading international organizations Canada belongs to:

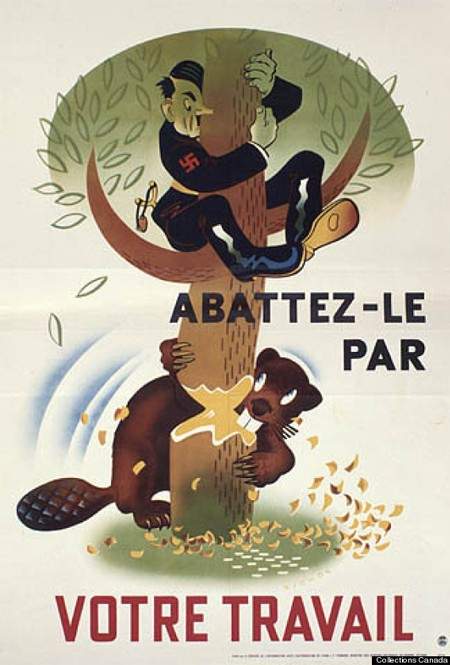

Anti-Authoritarinism

World War II remains the most popular and romanticized conflict of Canadian history, and Canadians still express great feelings of pride in having helped topple the murderous dictatorships of fascist Germany and imperial Japan. Since then, the idea that Canadian foreign policy should be primarily geared towards the eradication of authoritarianism, totalitarianism, imperialism, terrorism, and other oppressive and tyrannical “-isms” has proven particularly powerful.

Officially, at least, many of Canada’s recent wars have been justified on the basis of helping curb dictatorial abuses in other parts of the world. The Korean War saw Canadians fight against the armies of the Communist dictator Kim Il Sung (1912-1994), the Persian Gulf War (1991) centred around expelling the forces of Iraqi despot Saddam Hussein from Kuwait, the 10-year war in Afghanistan (2001-2011) pitted Canadians against terrorists allied with the fundamentalist Taliban movement. Today, Canadians continue to assist in global counter-terrorism campaigns against violent extremist organizations like Al-Qaeda and ISIS.

One can certainly debate whether Canada’s only interest in fighting these various regimes was to free oppressed foreign peoples from tyranny; obviously, there were larger geopolitical and economic interests at play, too — just as there were during World War II. Regardless, the idea that Canada always fights on the side of democracy and freedom remains a source of great patriotic pride, and helps give a theme of consistency and idealism to the country’s 90-year history of independent foreign policy.

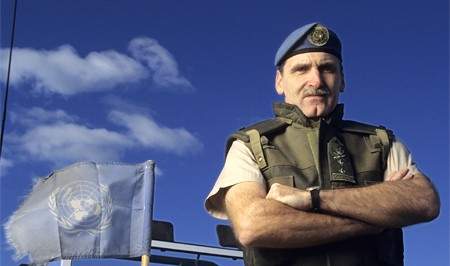

Canadian Peacekeeping

For a long time, the idea that Canada was primarily a peacekeeping nation was one of the country’s most venerated ideals, celebrated in everything from national holidays and monuments to beer commercials and the ten dollar banknote. In recent years, however, the very idea of what “peacekeeping” is, and whether Canada’s actually any good at doing it, has become more controversial and debated.

In 1956, three of Canada’s closest allies – France, Britain, and Israel – all went to war with Egypt over that country’s controversial nationalization of the Suez Canal. In the aftermath, Canadian foreign minister (and future prime minister) Lester Pearson (1897-1972) spearheaded the creation of a United Nations Emergency Force, consisting of troops from several neutral countries, to separate the combatants until a diplomatic solution to the Suez crisis could be reached. In the decades following, Canadian soldiers under U.N. authority served in several other peacekeeping missions inspired by the Suez experience, most notably in Congo (1960-1964), Syria (1974-2014), and Cyprus (1964- ). Honouring Pearson’s original vision, these Canadians served (and continue to serve) mostly as neutral mediators, not combatants, and helped separate or monitor warring factions without taking sides.

Peacekeeping proved an attractive way for Canadians to stay actively involved in foreign affairs while retaining a small military and preserving the country’s reputation of independence from the major powers. It was, as some pundits were fond of saying, a great way for Canada to “punch above its weight.” Beginning in the 1990s, however, Canada quietly began to agree to fewer and fewer peacekeeping missions, in part because the United Nations was starting to fall into lower repute due to a string of failed missions in Somalia (1992-1995), Rwanda (1993-1994), and Iraq (1991-2003), but also because the Canadian defence department was losing interest in small, open-ended troop commitments. Since the NATO-led war in Kosovo (1999), and especially since the 2001-2011 war in Afghanistan, Canada has become more comfortable taking sides and fighting in an openly combative role, in what some mourn as a loss of identity and others claim is just a restoration of an older foreign policy tradition.

A Canadian solider trains members of the Afghan National Police in Kandahar Airfield in 2011.

Cpl Tina Gillies/DND-MD

Economic Interests

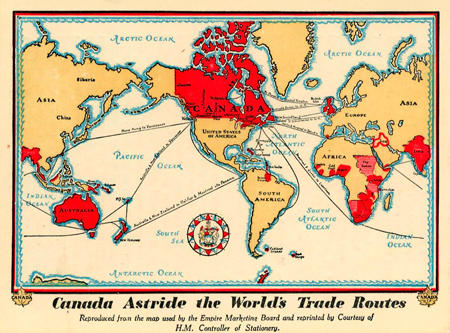

Canada is a rich country, and part of that wealth flows from a vast array of profitable Canadian economic relationships all over the planet. Home to an incredibly globalized economy, Canada has formal free trade agreements with many countries, and Canadian individuals and businesses have substantial investments, stores, offices, warehouses, mines, factories, and other property holdings in dozens of countries around the world. This means a significant amount of Canadian foreign policy is devoted to preserving the global economic conditions that generate wealth for Canadians.

Canada’s enormous dependence on U.S. trade for consumer goods and jobs, for instance, has been largely credited (or blamed) for the country’s generally pro-American position on most major foreign policy issues over the years, a fact which can often heighten the already ample levels of Canadian insecurity regarding the U.S.-Canada relationship. The same is largely true of Canada’s relationship with dictatorships like China and Saudi Arabia, which remain similarly warm largely for trade reasons, but also require looking the other way on human rights abuses in order to maintain.

Most Canadians generally understand that their government must maintain ties to some distasteful regimes and take advantage of unpleasant or exploitative business practices such as sweatshops and lax labour laws in order to provide Canadians with the standard of living they have come to expect. Which is not to say such facts can’t still be unsettling when they make the headlines.