No

20th Century History of Canada

After years of political turmoil, the late 19th century saw four of Britain’s North American colonies unify into a single, self-governing confederation called Canada. As the century concluded, this confederation proceeded to expand to the east and north, eventually taking over the entire northern half of the continent.

Economic Growth

Originally a nation of farmers, fishermen, loggers, and fur traders, the dawn of the 20th century saw a full-scale transformation of Canadian society. As new provinces were settled, new cities began to spring up, and by the 1910s half of all Canadians were living urban, rather than rural lives for the first time. The development of new machines under the frantic period of late-19th century modernization known as the Industrial Revolution saw a dramatic growth in city-based factory work. Canada’s raw natural resources were now being processed into useful products such as lumber, textiles, and meat — creating all sorts of new jobs that got people off the farm and out of the woods.

A massive influx of immigrants, intended to settle uninhabited parts of the Canadian west, helped change the fundamental ethnic makeup of the country. No longer simply French and English, large numbers of Canadians were now Irish, Italian, Polish, Ukrainian, Dutch, or Scandinavian — and even some Chinese and Japanese, too. To this day, the 10 years between 1906 and 1916, when Canada welcomed some two million new residents, remain the country’s largest population boom.

Under the 15-year leadership of Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier (1841-1919, served 1896-1911), Canada pursued policies that yielded great economic growth, and a rising standard of living for almost everyone. True, a few rich folk at the top were getting much richer than everyone else — and much faster — but compared to the state of much of the rest of the planet, things in Canada seemed to be going quite well indeed.

Canadian World War I soldiers marching past Stonehenge in England, en route to France.

Glenbow Museum

World War I (1914-1918)

In 1914, Germany invaded Belgium, which forced Britain to go to war with Germany due to an alliance the Brits and Belgians had at the time. It was a confusing war without much obvious relevance to Canada, yet all British colonies were promptly expected to fight alongside the motherland. Canada received an awkward reminder that despite the country’s emerging status as one of the wealthiest, most industrialized, modern societies on earth, it was still a mere colonial possession of a much stronger empire, unauthorized to run its own foreign affairs.

The French-Canadian residents of Quebec were particularly resentful. They had no interest in fighting “English wars” and viciously opposed efforts by the federal government to impose a national draft. More than 650,000 Canadians would fight in Europe, but they were overwhelmingly of English heritage. The Canadian prime minister of the time, Robert Borden (1854-1937, served 1911-1917), was a strong backer of Britain’s war effort, but was simultaneously skeptical of London’s sense of entitlement regarding the service of colonial troops. Behind the scenes, he pointedly insisted that if Canadian soldiers were going to be used to fight the Empire’s wars, Canada’s government should have greater say in how those wars were fought.

Canadian soldiers, in any case, performed exceptionally, making heroic contributions on key European fronts, most notably the Battle of Vimy Ridge in France (1917), where more than 3,000 Canadians were killed. The sacrifice of so much Canadian life abroad solidified opinion back home that Canada was a mature nation in its own right, and deserved to be recognized as such.

Canada Earns Its Independence (1918-1931)

In the aftermath of the First World War, successive Canadian governments, backed by the governments of other self-governing white British colonies like Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, and South Africa, aggressively lobbied Britain to restructure the Empire to allow its colonies greater independence. In 1926, an Imperial Conference in London featuring all the colonial prime ministers declared that Britain and its dominions were, in fact, “equal in status,” and not master and subject. In 1931, following further negotiation, the British Parliament passed a law known as the Statute of Westminster which formally surrendered Britain’s ability to make laws for Canada.

No longer an Empire, it was said the self-governing white colonies now formed a “Commonwealth” of friendship in which they shared allegiance to a common king, but enjoyed full independence in domestic and foreign policies. For all intents and purposes, Canada was now an independent country, with Britain only retaining a few increasingly symbolic powers.

Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

After a brief economic boom in the 1920s, a severe, worldwide economic collapse — dubbed the Great Depression — hit Canada hard in the 1930s, putting millions out of work and plunging millions more into miserable poverty, particularly on Prairie provinces where hardships were compounded by the so-called Dust Bowl drought. Desperate Canadian workers and voters became drawn to revolutionary ideas and wild new political parties. It was a time of radicalism, but the outcomes were not always destructive. Early feminist protests earned Canadian women the right to vote in elections across the country, and union activists — who began exercising their right to strike — helped abolish child labour and secure safer factories.

In 1939, Britain again declared war on Germany, which was now run by the fanatic dictator Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), and though Canada was no longer automatically obligated to follow suit, pro-British sentiment in the country remained strong. The government of Prime Minister Mackenzie King (1874-1950) passed a supportive declaration of war against Germany a week later, and Canadian troops were once again sent to Europe. When Britain declared war on Germany’s Asian ally Japan in 1941, Canada again followed, and the conflict expanded to the Pacific Ocean.

The Second World War — Canada’s first to be fought under Canadian command — involved a massive mobilization of people and resources, both at home and abroad. More than a million Canadians served in their country’s armed forces, while the wartime production of ammunition, armaments, and vehicles gave an enormous boost to Canada’s suffering economy. Overseas, Canadian troops again demonstrated great bravery playing a critical role in several key fronts, notably the failed battles of Hong Kong (1941) and Dieppe (1942), and the more successful invasion of Sicily (1942), and liberation of the Netherlands (1944-45).

Though the war’s end in 1945 was a time of considerable celebration across Canada, an uncomfortable fact remained: the bulk of Canada’s fighting had been done by English-Canadians. As had been the case with the First World War, French-Canadians once again largely opposed participating in what they deemed an “English” conflict, and vigorously opposed a national draft. Canadians of Japanese decent, meanwhile, had found themselves on the receiving end of vicious wartime racism, culminating in Prime Minister King’s 1942 decision to round up all citizens of Japanese descent and place them in internment camps in rural communities, where they would supposedly pose no danger to whites. The episode remains one of the country’s darkest chapters and the government of Canada officially apologized in 1988.

The Post-war Boom

World War II had changed Canada, both in terms of economic development and national pride. Wartime industrialization dramatically grew the manufacturing sector of Canada’s economy, allowing the country to become a world leader in industries like car-building and chemical processing, while the 1947 discovery of oil in the province of Alberta put Canada on the map as one of the planet’s major petroleum producers. As education became more affordable, more Canadians were able to pursue careers in new, non-physical sectors of the economy, such as science, finance, engineering, media, and of course, an ever-growing government bureaucracy.

All of this allowed more Canadians than ever to enjoy comfortable, middle class jobs and lifestyles, and the growth of suburban communities in previously empty areas surrounding the cities, where mom, dad, and the kids could live in small houses with their own yard, car, and white picket fence, reflected the new standard of Canadian living.

Canada’s post-war governments of the 1950s and ’60s wrapped up the final, mostly symbolic loose ends of securing complete political independence from Great Britain. In 1952, Canada said goodbye to its last British-appointed governor, the Viscount Alexander (1891-1969), and turned the office into a figurehead position to be filled by Canadian citizens. The dominion of Newfoundland on the Maritime coast, which was a self-governing British colony, agreed to join the Canadian confederation in 1949, giving Canada its 10th province — and present-day borders. After much debate, in 1965 a uniquely Canadian flag, the Maple Leaf, was adopted, and the Union Jack was lowered from Canada’s Parliament.

Postwar foreign affairs quickly became dominated by fears of the Russian-led Soviet Union, which had grown large and powerful in the aftermath of the war. Fear of a Soviet takeover of the world through its style of Communist philosophy and government spawned a decades-long Cold War (1945-1991), in which the United States led the “free world” in opposition to communist regimes. In 1949 Canada joined the US-led military and political alliance known as NATO to help oppose Russian expansion and beginning in 1963, dozens of US nuclear weapons were stationed in Canada . At the same time, successive Canadian prime ministers worked equally hard to earn Canada a reputation as a moderate, compassionate “middle power,” skilled at diplomacy and negotiation in the tense Cold War climate. Though more than 500 Canadians would die fighting Communist forces in the Korean War (1950-1953), Canada’s refusal to participate in the American-led Vietnam War (1964-1973) against the Communist armies of North Vietnam earned the country a reputation for caution and restraint.

The Conflict with Quebec

Ever since their conquest by the British in 1759, the French-speaking residents of Quebec struggled to maintain their unique culture in face of English pressure to assimilate. For 200 years, this hostility and insecurity played out in the form of an ultra-conservative, extremely Catholic, largely feudal, agrarian society that shut itself off from much of the modernization that had occurred in the rest of Canada. As had been the case for centuries, much of the province’s wealth remained concentrated in the hands of a few rich English families.

It was not until the mid-20th century that the old ways began to break down. After the death of Maurice Duplessis (1890-1959), Quebec’s long-serving ultraconservative prime minister, French-Canadian society underwent a phase known as the Quiet Revolution, which saw a new generation of politicians and educated professionals aggressively modernize the province. Post 1960s, Quebec became more secular and industrialized, while a slew of new businesses put more wealth into French-Canadian hands. “Masters in our own house” was the slogan of the time.

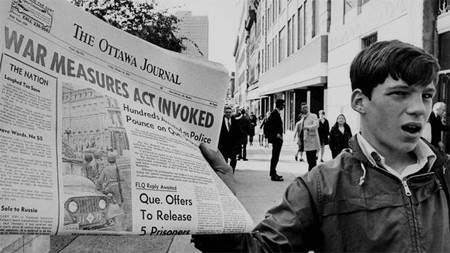

Yet many Quebecers felt things were not improving fast enough. Separatism — the idea that Quebec was too different from the rest of Canada to exist as a province, and could only realize its full potential as an independent country — began to grow in popularity after the war, spurned by economic difficulties and a growing sense of self-reliance. A certain radical vein of Quebec separatists turned to Marxism and violence, with a terrorist group known as the Front de Libération du Québec setting off dozens of bombs in government buildings and other high-profile targets across the province throughout the 1960s. An openly separatist Quebec government, led by Premier Rene Levesque (1922-1987), was elected in 1976, and a referendum on separation from Canada was held in 1980. It failed, but the dynamic of Canadian-Quebec relations was forever changed.

A New Constitution (1980-1993)

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, a charismatic, progressive, and often authoritarian figure who led Canada for nearly 16 years between 1968 and 1984, nearly single-handedly determined Canada’s political priorities during the 1970s and ’80s — even after he left power. A Quebecer himself, Trudeau believed that much of Canada’s French-English tension could be alleviated under a new Canadian constitution that protected Quebec’s French language and culture, while also enshrining the principle that all citizens were equal under the law.

The result of years of intense negotiation with the provincial premiers, Trudeau’s new Constitution Act of 1982 did not change Canada’s system of government, but contained a Charter of Rights and Freedoms that finally enshrined the basic civil rights of all Canadians, including freedom of speech, religion, and movement, and declared Canada a bilingual nation where all citizens had a right to speak either French or English. Perhaps most importantly of all, the Constitution Act was also the final law Britain would ever pass for Canada; following its approval, the British Parliament agreed to surrender its control of Canadian constitutional law — its last remaining power over the country.

The separatist government of Quebec had opposed the new constitution and was the only province that refused to sign it. Trudeau’s successor as prime minister, Brian Mulroney (1939-2024, served 1984-1993), embarked upon two ambitious campaigns to revise the Constitution Act in a way that would finally please the French province, but both efforts ultimately failed after long, polarized national debates. Quebec’s signature remains symbolically absent from the Canadian Constitution to this day. Capitalizing on the dissatisfaction of the constitutional talks, in 1995 Quebec’s government held a second referendum on separation from Canada and it only failed by a margin of less than one per cent.