No

19th Century Canadian History

In the early history chapter, we left off with the British army having conquered the French colony of Quebec, placing thousands of worried French settlers under uncertain English rule. Meanwhile, the 13 British colonies of New England had declared independence as the United States of America, which sent a bunch of English-speaking Loyalists northward, looking for somewhere to live that was still under British rule. They found Quebec. To achieve peace in their now uncomfortably diverse colony, in 1791 the Brits chopped Quebec in half, making one colony into two: Upper Canada for the English, and Lower Canada for the French.

The War of 1812

Though the British had promised to respect the independence of the United States of America in the aftermath of the Revolutionary War (1775-1783), Anglo-American relations remained tense and disrespectful in the early 1800s. The British Navy routinely harassed American ships that tried to trade with England’s arch-nemesis France, seizing American cargo or kidnapping and drafting American sailors into British military service.

A certain faction of American politicians (sometimes dubbed the War Hawks) soon began calling for a “Second War of Independence” against England, with British forces stationed in the Canadian colonies being the most obvious target for a preemptive strike. It was a controversial proposal. The United States of those days was a small, financially-struggling nation ill-equipped for a rematch with the most powerful empire in the world, and many Americans worried a ill-conceived war with England would wind up weakening their independence, rather than strengthening it. But the Hawks won the debate, and in June of 1812 the U.S. Congress voted in favour of war.

When fighting broke out, bad behaviour on both sides reinforced initial suspicions. The rapid American invasion of Quebec stirred fears that the American government had nothing less than the complete conquest of North America in mind, while the corresponding British invasion of Washington, D.C. heightened fears that America’s hard-won independence was in danger of being lost. Despite two years of heavy fighting, by 1814 it was clear no one was getting any closer to victory, and a ceasefire was called. The peacemaking Treaty of Ghent did little beyond restore the pre-war status quo, with neither side gaining any territory. As historians like to call it, it was the “war nobody won.” It did, however, herald the start of a new era of peace between Britain and the United States, and the end of territorial threats to Canada. In 2024 Canada will celebrate 200 years of peaceful relations between Canada and the United States — one of the longest eras of peace between two neighbouring countries anywhere on earth.

The Rise of Democracy (1820s—1850s)

Up to this point, the Canadian colonies had very authoritarian, aristocratic colonial governments. Though small elected parliaments were introduced to the colonies in the late 1700s, these were weak by design, and all real power remained in the hands of the British-appointed governor. This was fine when the colonies were filled mainly with poor farmers and fur traders, but by the 1820s, Upper and Lower Canada were becoming larger, richer, and more diverse societies. A swelling population and steady economic growth saw the rise of a substantial middle class comprised of people like merchants, carpenters, doctors, lawyers, and journalists — all of whom demanded a greater say in how their colony was being run.

The 1830s saw the Canadas enter a considerable period of political unrest, with a well-organized group of Reformers, led by mostly middle-class professionals, rallying against the corruption and authoritarian rule of the so-called Family Compact, the clique of wealthy, British-born landowners who surrounded the governor and influenced his priorities. Though all were pro-democracy, what type of democracy the Reformers wanted varied. Some merely wanted stronger elected assemblies and a system of government more like Britain’s. Others, however, went much further and wanted the Canadas to either abandon British rule altogether or join the United States.

The Reformers staged several small armed rebellions as part of their protests, taking to the streets, brandishing weapons, and torching buildings. The riots were easily put down by British authorities, with the leading provocateurs either jailed, hung, or exiled to Australia, but the British government was spooked. In 1838, an English politician named Lord Durham (1792-1840) was appointed emergency governor of Upper and Lower Canada and wrote a famous report on the political situation in the colonies. He reached two big conclusions: the colonies needed a more democratic system of government, and the French colonists, who had produced the most radical Reformers, needed to be better assimilated into English society. As a solution, he advocated the British end all government support for French culture — including any official support for the French language — and merge Upper Canada and Lower Canada into a single colony governed by a British-style parliamentary system. In 1841, Britain passed the Act of Union, which created the United Province of Canada, and Durham’s vision came true.

"L'Assemblée des six-comtés," a painting depicting the eve of an 1837 rebellion in Lower Canada.

The United Province of Canada (1841-1867)

The Act of Union introduced a joint parliament to Canada, in which English and French Canadians were allowed to elect an equal number of seats. The British governor, in turn, agreed to appoint the most popular political leaders from each community (sometimes called the joint premiers) to run a cabinet overseeing the day-to-day management of colonial government. Canada had now more or less become a parliamentary democracy, but not everyone was satisfied. The French Canadians were keenly aware that this new system of government had been explicitly designed to subordinate and assimilate them, and in election after election French voters accordingly elected radical Reformers to parliament who denounced the political system as a scam and constantly delayed or opposed legislation proposed by the more conservative English Canadian politicians. Though the joint parliament was supposed to foster cooperation, it soon became impossible to get anything done.

Meanwhile, similar things were going on in Britain’s Maritime colonies, a small collection of islands and peninsulas on the Atlantic coast that were governed separately from the Canadas. Initially sparse and underpopulated, an influx of Loyalist migrants had flooded the colony of Nova Scotia after the American Revolution, and in 1784, a chunk was split off to form the new colony of New Brunswick. Like the Canadas, these colonies experienced similar bouts of political turmoil in the mid-1800s stemming from a lack of democratic government, but also born from a dire economic situation far worse than anything on the mainland.

From 1861 to 1865, the United States fought a bitter Civil War between its northern and southern states over the legality of slavery. The British government backed the slave-holding South in an effort to weaken U.S. power, which did not do great things for U.S.-British relations when the North eventually won. The Americans began to once again see the Canadian colonies as a possible staging ground for British subversion or attack, with some U.S. politicians openly calling for the lands to their north to be annexed or invaded.

The Confederation Deal (1867)

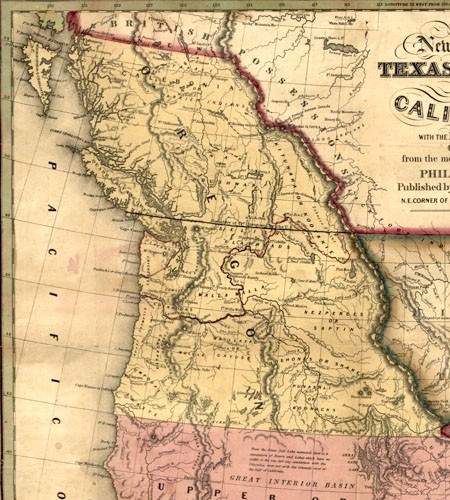

During the mid-19th century, Britain became preoccupied with expanding its empire in India and Asia and began to lose interest in Canada, which was no longer seen as all that financially or strategically important. This put pressure on Canadian politicians to come up with their own solutions to their political problems, and by the 1860s some of them began to push for the idea of merging all of England’s remaining North American colonies into a unified, jointly-run, self-governing colonial confederation. This would give the colonies improved economic and military strength born from their combined land and resources, while also granting greater local government powers to groups like the French Canadians, who clearly wanted more control over their own affairs. A series of colonial conferences were held, and members of the parliaments of the United Province of Canada and the Maritimes discussed and debated what a proposed federation of British North America should look like.

Inspired by the United States Constitution, but also eager to avoid a repeat of the American Civil War, the colonial politicians eventually agreed that their confederation should have a single federal government run by an elected parliament and prime minister, while also allowing each member colony to retain its own local parliament and prime minister, too. The unified federal government would be strong, with the power to make all criminal laws and regulate matters of national importance like currency, trade, and defense, while the individual colonies — now known as provinces — would retain control over local matters like education, housing, and natural resources. A draft constitution for the proposed confederation was agreed upon at the Charlottetown Conference of 1864, and approved by the British government on July 1, 1867. A new, self-governing mega-colony known simply as the Dominion of Canada was formed. The old United Province of Canada was once again split into two pieces, with the English half becoming the province of Ontario and the French part becoming the province of Quebec, each with their own parliaments. They were joined by the Atlantic colonies of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia as Canada’s first four provinces.

"The Fathers of Confederation," one of the most famous paintings in Canadian history, by Robert Harris (1849-1919).

Growth of the New Dominion (1867-1905)

Today, Canadians celebrate July 1st as the national holiday of Canada Day — the day Canada “became a country” — but the confederation deal of 1867 was not really understood that way at the time. While the new dominion government represented a decisive solution to years of political unrest, Canada remained a colonial possession of Britain, albeit an increasingly self-reliant one. Though Canada had gained control over most of its internal affairs, London still retained a number of important powers. It was up to the new dominion to prove they could be trusted with more.

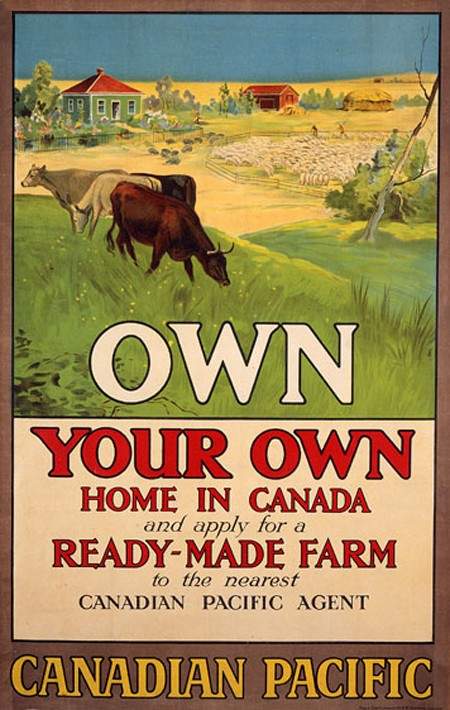

Canada’s first prime minister was a tough, hard-drinking Scot named John A. Macdonald (1815-1891), who had served as a leading conservative politician in the United Province and was a lead negotiator in the confederation debates. A man of enormous ambition, vision, and ego, Macdonald wanted an even bigger Canada than the one he was given, and eagerly set upon expanding the confederation’s borders in all directions. The cornerstone of his plan was the construction of a giant trans-continental railroad — known as the Canadian Pacific Railway, or CPR — linking the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic, which he knew could help significantly increase immigration and settlement in Britain’s largely unexplored territories of the west and north, which could then be absorbed into Canada as new provinces.

In 1870, the self-declared government of the British territory of Manitoba, located in the midst of the wilderness in the vast western prairies of central North America, and ruled by the charismatic and eccentric Louis Riel (1844-1885), agreed to become Canada’s fifth province. They were followed in 1871 by Britain’s Pacific coast colony of British Columbia, who threw their lot in with Canada after receiving Macdonald’s assurance that his railroad would reach them. Two years later, the tiny Atlantic island colony of Prince Edward Island became province number seven. The Islanders had cockily refused to join confederation in 1867, but by 1873 they were so heavily in debt they had little choice.

By now, the fur trade had rapidly declined, and in 1868 the once-mighty Hudson’s Bay Company agreed to surrender their control of much of northern North America — the Rupert’s Land territory — to Macdonald. These new lands, which more than doubled Canada’s size, were renamed the Canadian North-West Territory in 1870. By 1905, settlement to the NWT had increased to the point where its previously vacant southwestern regions could be carved into provinces eight and nine: Alberta and Saskatchewan. Canada now stretched unbroken from sea to sea to sea to sea.