Chapter

No

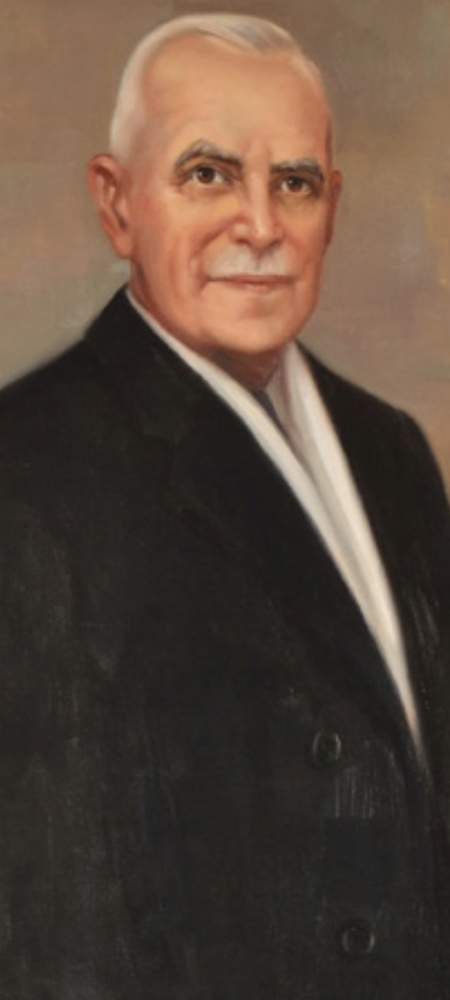

Louis St. Laurent

Dubbed “Uncle Louis” for his gentle, square style, Louis St. Laurent was an icon of the relative peace and prosperity that defined Canadian society in the aftermath of World War II (1939-1945). Though his tenure is not widely remembered today, the St. Laurent years were actually a time of quite substantial foreign, domestic, and constitutional achievements.

St. Laurent came to politics late in life, and was specifically recruited by Prime Minister Mackenzie King (1874-1950) to serve as attorney general, and later foreign minister, in his wartime cabinet. A respected French-Canadian lawyer with strong Anglo loyalties, during the war he sought to stem anti-Canadian sentiment in his home province of Quebec with mixed results. When King resigned in 1948, St. Laurent was his hand-chosen successor.

Prime Minister St. Laurent continued King’s agenda of earning Canada ever-greater concessions of symbolic and political independence from Britain. In 1949 he ended Canadian legal appeals to the British House of Lords, making the Supreme Court of Canada the country’s highest court, and 1952 appointed the country’s first-ever Canadian-born governor general. After elaborate negotiations, on March 31, 1949 Canada welcomed the Dominion of Newfoundland as the country’s 10th province — making St. Laurent the first PM since Wilfrid Laurier (1841-1919) to expand the nation’s borders.

A strong internationalist, St. Laurent sent over 26,000 soldiers to fight in the United Nations-led Korean War (1950-53) to repel a Communist invasion of South Korea, but pointedly refused to support the British side in the Suez War of 1956, instead siding with the neutral United States. His foreign minister, Lester Pearson (1897-1972), helped supervise the terms of the postwar peace deal, and in doing so helped Canada gain a new reputation as a pragmatic and helpful “middle power” during the Cold War (1945-1990).

Canada’s post-war years saw steady economic growth, but also the rise of a large and powerful federal bureaucracy. As St. Laurent’s second term progressed, there was increasing criticism that the country was being governed by an arrogant elite of professional experts, best embodied by the multitalented but bossy C.D. Howe (1886-1960) — St. Laurent’s right-hand man and so-called “Minister of Everything.” The St. Laurent administration’s rushed attempt to approve an enormous Trans-Canada Pipeline without much parliamentary involvement generated fiery outrage and conspiracy theories among the opposition, and in 1957 he lost his bid for a third term to conservative populist John Diefenbaker (1895-1979).