No

Early History of Canada

Canada, as we know it today, is a country born from the European fascination with exploration, imperialism, and colonization that began in the 15th century — though some Canadians can trace their roots back even further.

Aboriginal Canada

Although today the majority of Canadians are from white, European backgrounds, long before that the land that is now “Canada” was occupied for thousands of years by the aboriginal peoples of North America. These people lived on the northern half of the North American continent ever since homo sapiens first arrived from Asia, most likely via the Bering Land Bridge, around 21,000 B.C.

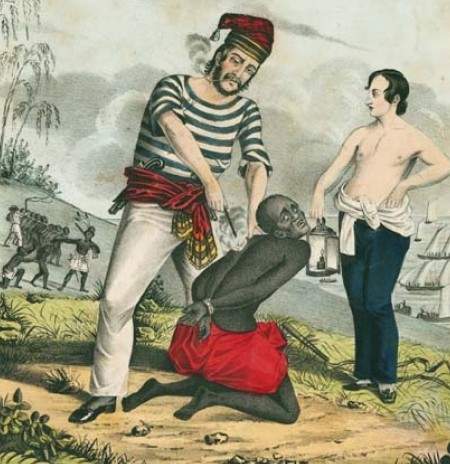

They were the Indigenous North Americans, also known as Indians, Amerindians, Native Americans, or First Nations, and they lived in small, nomadic groupings across all parts of modern Canada, even extremely inhospitable areas like the barren central grasslands and northern arctic. Over the course of centuries, these communities developed into organized societies that maintained sustainable economies, sophisticated political systems, complex spiritual beliefs, and rich, vibrant cultures.

Once European settlers began coming to North American in the 16th century, however, the continent’s indigenous peoples were systematically uprooted from their traditional homes and villages, either through war, forced relocation, or threats of violence, and pushed into remote areas where they wouldn’t be in the way of European colonization. Outgunned by European technology and uniquely susceptible to European disease, the vast majority of Canada’s aboriginal population quickly declined to a small minority as their death rate skyrocketed and European immigration increased. Though Europeans would often recruit natives to work as soldiers, hunters, and fur traders, Indigenous people were generally seen as a “lesser” race to whites, and were mostly disliked, mistrusted, and mistreated by them. New European-led governments would would often refer to the “Indian Problem,” and continued projects to make them go away, either physically or culturally, well into the 20th century. Only very recently have the descendants of the first peoples of Canada begun to enjoy equal and dignified treatment under Canadian law.

You can learn more about Canada’s aboriginal people in the First Nations chapter.

Exploration and Colonization (1534-1756)

New France

Canadians are taught to peg the symbolic start of Canada’s European settlement to 1534, when a French explorer named Jacques Cartier (1491-1557) sailed across the Atlantic Ocean from Europe and entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence. As the traditional story goes, he planted a giant crucifix into the shore of what is now Gaspé, Quebec, claiming all he could see for the King of France.

Ambitious though he was, Cartier’s attempt to establish a permanent settlement in North America failed, and it was not until 1603 that another French explorer, Samuel de Champlain (1567-1635), really got things going. A zealous missionary, expert navigator, savvy political leader, and visionary nation-builder, Champlain presided over the founding of a colony called New France that sat along the coast of the St. Lawrence. As governor, he created several permanent cities for French farmers, fishermen, and fur-traders, most notably Quebec City (1608) and Trois-Rivières (1634), as well as Port-Royal (1605) on the Acadian Penisula (home of the modern day Maritime provinces). His death failed to slow things down, and in 1642 New France’s new governor established the settlement of Montreal (1642), destined to be one of Canada’s most important cities.

Buoyed by their success in New France, the French gradually moved west from the St. Lawrence coast towards the Great Lakes and then traveled down the Mississippi River. In 1682, they claimed much of the middle of North America, including the Mississippi Basin and Ohio Valley, as a massive French territory called Louisiana, where they began establishing more cities and settlements.

New England

The British, meanwhile, landed in North America around the same time as Champlain, and quickly set about building thriving little colonies of their own in an area just south of New France and east of Louisiana. Starting with the famous settlements of Jamestown (1607), Plymouth (1620), and Boston (1630), the British would eventually build an impressive set of 13 colonies occupying most of the eastern coast of North America, from Massachusetts in the north all the way down to Georgia in the south.

For both strategic and economic reasons, the British were also interested in claiming territory to the north of New France. In 1670, after a path to enter North America through the north via Hudson’s Bay was discovered, England audaciously declared ownership of the entire northern coast of the continent, which they named Rupert’s Land. In contrast to the 13 colonies, which had large populations and a moderate degree of self-government, Britain allowed control of the vast and underpopulated Rupert’s Land to be controlled entirely by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), a private corporation headquartered in London. Managing so much land gave the HBC enormous wealth and political power, and in time it began to function as its own empire, largely independent of the British government.

The Fur Trade

In the early colonial period, both the French and English colonial economies were based around killing animals and selling their skins back to Europe, where clothing companies made them into fashionable hats and sold them to rich people. This was known as the fur trade, and it quickly became a source of enormous rivalry between the French and English empires, both of whom wanted to conquer more and more of North America and thereby control more and more of the fur market.

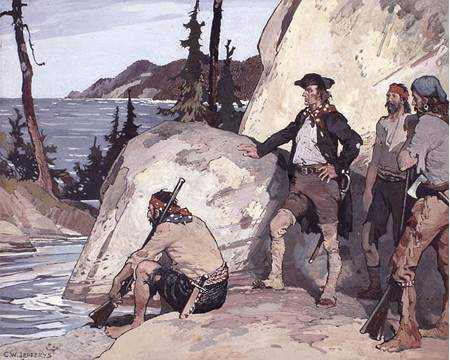

Armed conflict between rival groups of traders broke out almost immediately, and the years between 1613 and 1756 are known as the era of the Fur Wars, marked by near-constant violence between French, English, and aboriginal forces as everyone battled to seize land from one another or merely hold what they already had. This back-and-forth led to many brutal episodes, the most infamous being a 1755 British attack on France’s Fort Beauséjour on the Acadian peninsula, which led to the forcible deportation of all of that area’s French residents, known as Acadians, many of whom wound up relocating to Louisiana.

Britain’s Conquest of New France

Steadily worsening relations between France and England in North America (as well as back home in Europe) saw the small conflicts of the Fur Wars gradually escalate into an all-out war for total control of the American continent. Described as either the North American front of the European Seven Years War (1756-1763) or a purely North American conflict called the French and Indian War (1754-1763), it’s easily the most important military episode in Canadian history.

Going in, the two sides were relatively evenly matched. The British colonies had larger populations — and thus access to more colonial soldiers — but the majority of aboriginal tribes sided with the French. A series of large-scale, surprise French attacks on critical English settlements generated a string of early British defeats, prompting the British to import thousands of troops from Europe in an attempt to turn the tide. In 1759, the military commanders of the two colonial armies faced off in the decisive 30-minute Battle of the Plains of Abraham, with the British ultimately victorious.

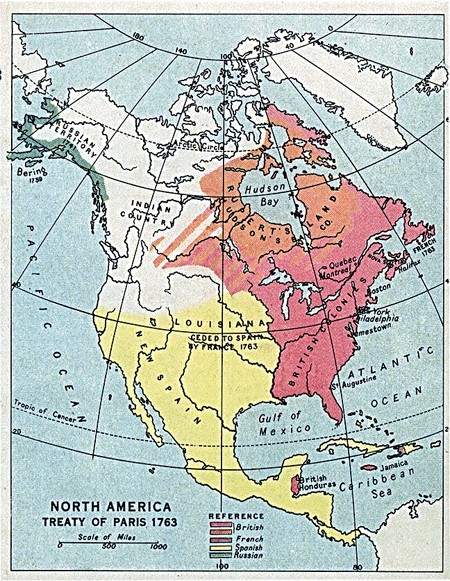

The Treaty of Paris (1763) that ended the war was devastating from a French perspective: all of New France and most of Louisiana was given to England, while the remaining scraps were — for complicated geopolitical reasons — given to Spain. French rule of North America had effectively ended. But the Brits weren’t completely sore winners. In 1774, New France was reorganized into a British colony called Quebec, governed by a charter known as the Quebec Act that promised to continue French law, protect the Catholic religion (which most French colonists practiced), and respect the unique French style of farming, known as the seigneurial system. Promising to honour these traditions was controversial in England and among English colonists in North America, as they were seen as being quite anti-British. But given Quebec’s large population was overwhelmingly French, the British government felt they didn’t have a lot of options if they wanted to maintain peace in their new French colony.

"The Death of Wolfe", a famous painting of British army general James Wolfe (1727-1759) dying on the Plains of Abraham.

The American Revolution

Controversy over the Quebec compromise quickly spread throughout the rest of British North America, and barely had the Seven Years War ended when unrest began to rumble in England’s 13 colonies south of the former New France. In the aftermath of the French defeat, many New Englanders resented the way their British rulers chose to handle the new political realities of North America, and grew particularly sour once the British government began limiting their ability to migrate and settle in England’s newly-acquired western territories in the former Louisiana. The war against France had also proven tremendously expensive for Great Britain, which led to dramatic and unpopular tax hikes on colonials and a scaling back of democratic rights to silence complaints.

In 1776, a group of influential New England politicians declared independence from Britain and launched a self-styled Revolutionary War (1775-1783) — backed by the government of France — that ended with the establishment of a new country on eastern North American free from British rule: the United States of America.

But not all of England’s colonies had been willing to join in. The English colony of Nova Scotia — the former French Acadia — sometimes called the “14th colony,” refused to participate, as did the conquered French subjects of Quebec. Both groups felt that despite England’s often oppressive rule, their rights and security were ultimately better trusted to stable, reliable Britain than the radical American rebels.

"Canada acceding to this confederation, and adjoining in the measures of the United States, shall be admitted into, and entitled to all the advantages of this Union; but no other colony shall be admitted into the same, unless such admission be agreed to by nine States."

Sec. XI of the Articles of Confederation (1781), the first U.S. constitution, allowed Canada to easily join the country.

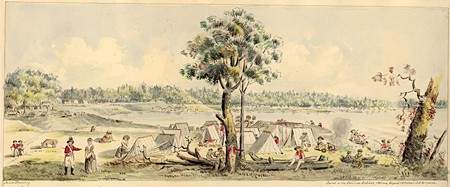

The Loyalists

The Revolutionary War was not universally popular in the 13 colonies, either. Like the Quebecers and Nova Scotians, around a quarter of the New England population did not support the idea of breaking with British rule, and after war broke out, many families fled northward to Quebec, seeking to live somewhere where England was still in charge. These migrants, dubbed Loyalists for their allegiance to Britain and its king, are some of the most romanticized characters of Canadian history, but their precise motivations remain debated.

The traditional interpretation has been to characterize the Loyalists as fundamentally conservative folk (dubbed “Tories” after the conservative faction in English politics), dedicated to the cause of monarchy, Empire, and social hierarchy, rather than revolutionary American notions of republicanism, democracy, and egalitarianism. This became a popular theory among those who liked to think of Canada as a more traditional and culturally British country than the United States. Contemporary historians, in contrast, tend to argue the Loyalists actually comprised a fairly broad cross-section of New Englanders encompassing a diversity of backgrounds and political views, united only in their desire to not live in a revolutionary war zone with a deeply uncertain future. This interpretation portrays Canadians as a cautious, practical people.

In any case, the Loyalist migration dramatically swelled Quebec’s English-speaking population in a few short years, causing great concern to the colony’s French residents who were already anxious enough about the survival of their distinct culture and traditions. In 1791, Britain attempted to alleviate these concerns by splitting Quebec into two colonies: Upper Canada for the English residents and Lower Canada for the French. Each colony would have its own government, in order to give it a bit of political and cultural independence from the distrusted people next door.