No

Social Issues in Canada

In recent years, one of the most defining elements of the Canadian identity has been the country’s social policies — the collection of laws and regulations that govern how Canadians live their lives, and what sorts of individual rights the government is willing to protect and defend.

Given that many Canadians like to focus on how their country is different from the United States, social policy is often seen as a window into the sort of values that make Canada a uniquely progressive country — though it would be a mistake to suggest all social policy is progressive or that progressive social policy has no Canadian critics.

Canadian Health Care

Whenever Canadians are polled about what makes them “proudest to be Canadian,” the Canadian health care system often tops the list. Beginning in the 1960s, Canada’s provincial governments began introducing government health insurance (sometimes known as medicare), to pay for hospital visits, operations, and other essential medical services. In 1984 the federal government passed the Canada Health Act which forced all provincial health plans to meet certain standards of coverage, and outlawed charging fees for medically-necessary services. Today, all Canadians are provided with comprehensive health insurance from birth through public health plans run by the various provincial governments (with funding help from Ottawa). The provincial governments now generally run most hospitals and clinics as well, with doctors and surgeons charging governments directly for their services. Very few privately-run hospitals or clinics exist in Canada these days.

Canada’s public health care system is one of the most generous in the world, but also quite expensive to maintain. In recent years, many provincial governments have started to scale back their scope of insurance coverage in order to make their medicare programs more financially sustainable, and Canadians often purchase supplementary private health insurance to pay for things like dentist trips, eye exams and any operation or treatment the government considers “non-essential.” Such plans, sometimes called extended medical coverage are often provided to working Canadians by their employers as a perk of the job. Private health insurance cannot — by law — pay for services covered by a provincial, public health plan, however.

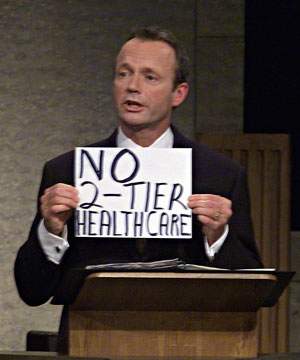

How to guarantee the long-term “survival” of the Canadian health care regime is one of the most heated debates in contemporary Canadian politics. On the right, it’s common to advocate greater privatization of medical services, including more privately-run, fee-based clinics and surgeons to give more choice to patients. Folks on the left, in turn, are generally extremely critical of anything that smacks of edging towards a so-called “two-tiered” system, where Canadians with money can buy their way into better medical care than those who use the public system. To the broader public, however, the status quo is considered nearly sacred, which leads most politicians to shy away from proposing dramatic reforms.

Abortion Laws in Canada

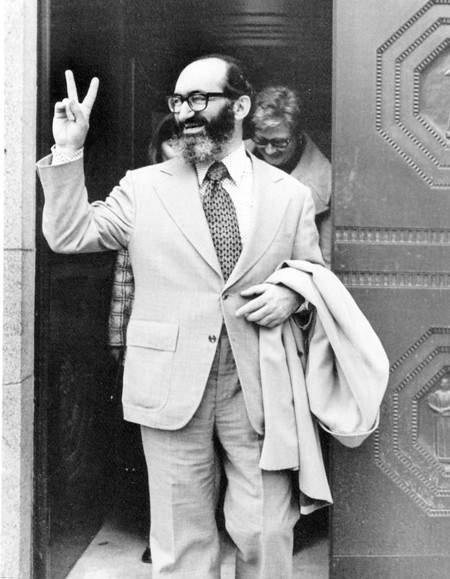

Owing in part to the pressures of the country’s large Catholic population, abortions in Canada were banned entirely until 1969, and then only permitted under narrow conditions when the mother’s health could be proven to be in danger. Illegal abortions continued in the background, however, and in 1988, a particularly unapologetic abortion surgeon named Dr. Henry Morgentaler (1923-2013) went before the Supreme Court of Canada to face charges. Siding with Morgentaler, the court ruled the country’s existing abortion regulations represented an unconstitutional burden on the rights of women, and the legal restrictions on the procedure were struck down.

Though the Supreme Court’s ruling said it would be permissible for the government to place some limitations on abortion, no Canadian government ever has. Canadian women thus have a universal right to abort at any stage of pregnancy — even the final weeks — which is a degree of permissiveness largely unseen elsewhere in the western world. At the same time, however, there do exist some de facto limitations on abortion determined by the ethics of individual doctors. In many parts of the country it can be difficult to find doctors willing to perform so-called late term abortions.

Abortion is a very controversial topic in contemporary Canada, and tops the list of things to avoid discussing in polite company. There are a number of passionate pro-life and pro-choice activist groups all over the country, prone to staging aggressive demonstrations and protests in order to ensure their opinions are heard. All of Canada’s political parties are officially pro-choice, however, and proposals to change Canadian abortion policy are almost never heard in mainstream political discussion. Since the 1990s, there has been a strong consensus among Canada’s party leaders that the “abortion debate” is a topic too politically explosive to reopen, so the status quo stays. This political consensus masks the degree Canadians themselves disagree about the issue however — a 2018 poll found Canadians quite evenly split when it was asked whether “there should be laws on abortion in Canada.”

Drugs and Alcohol

Liquor was associated with all sorts of social ills in early Canada, and at various times during the early 20th century most provinces experimented with banning the sale and production of alcohol in various ways. This era of so-called prohibition was not the magical solution many had hoped for, however, and by the 1920s, most provinces had changed their laws to re-allow the sale of alcohol, but only within certain tight regulations. To this day, Canadian provinces will often have complicated rules governing just how or where booze can be sold; in some provinces it may only be sold by special government-run liquor stores, in others the law may require hard alcohol and beer to be sold at different locations. Almost all forbid the sale of liquor at 24-hour shops like supermarkets and corner stores. Provinces generally allow citizens to brew (but not sell) their own beer and wine, but it is against federal law to make distilled liquor without a permit.

Canada’s legal drinking age is set by the provinces. In Alberta, Manitoba and Quebec the age is 18, everywhere else it is 19. Most provinces also have strict laws against consuming alcohol in public places and low standards for what constitutes “driving while under the influence.”

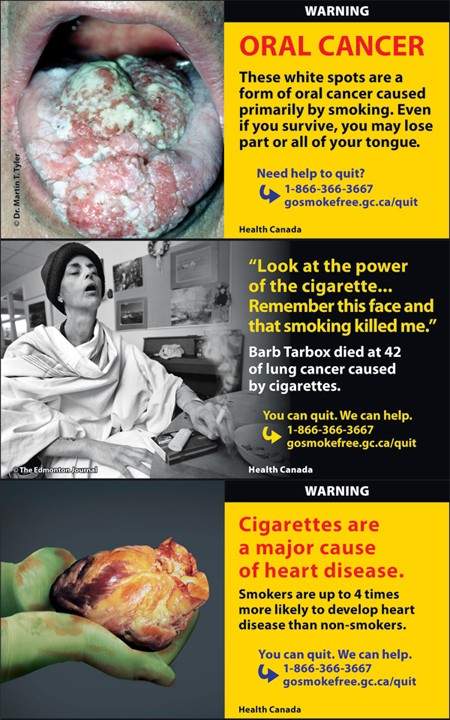

Marijuana was legalized for personal consumption across Canada in the fall of 2018. In theory, there are a lot of strict laws dictating exactly when, where and how marijuana can be bought, sold, and used, but it’s unclear to what degree these rules will be enforced. Prior to 2018, Canada’s anti-pot laws were rarely enforced and offenders rarely faced serious punishment, particularly in big cities. Since 2001, it has been legal for Canadian doctors to prescribe marijuana for medical reasons, and in 2014 the federal government authorized the licensing of private retail distribution of medicinal marijuana — a decision which triggered a dramatic increase of pot shops in urban centres, most of which promote rather hazy definitions of “medically necessary” pot.

Hard drugs like heroin, cocaine, LSD, and meth are all banned in Canada.

Freedom of Speech in Canada

Canadians generally take their constitutionally-protected right to free expression (the freedom to say or write whatever you want) very seriously, but the privilege is not an absolute one. As discussed in the Canadian Constitution chapter, Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms allows “reasonable limits” to be placed on most civil rights, and over the years the government has used this authority to pass some legal limits on freedom of speech. Canada has relatively uncontroversial laws that forbid spreading deliberate, malicious lies about other people (known as slander or libel) as well as copying or attempting to profit from other people’s ideas (copyright infringement). It is also generally against the law to use speech to encourage, advise, or provoke the committing of crimes.

It is still technically illegal to sell or produce obscene material in Canada and the Canadian government often bans the import of specific magazines, books, comics, containing very extreme depictions of sexual violence or perverted sex acts like incest or pedophilia. More “mainstream” pornography is only available in specially licensed stores or theaters, though this has obviously become far less relevant in the internet age. Provincial governments have similar laws banning children from buying pornography, excessively violent video games, or tickets for movies with “mature” content

- Canada Border Services Agency’s Policy on the Classification of Obscene Material

- Movie Ratings in Canada, Parent Previews

Canada has hate speech laws that make it a crime to publicly incite “hatred against any identifiable group” such as racial, religious, or sexual minorities, through written statements or other forms of media. There are exemptions for matters of sincere opinion or religious belief, and the attorney general of Canada must generally choose to initiate prosecution. More sweeping laws that made it a crime to “expose a person or persons to hatred or contempt” on the basis of identity were abolished in 2014. Sentences for the most extreme forms of hate speech, particularly hate speech that “promotes genocide,” can reach a maximum of two to five years in prison. New national security legislation makes it a crime to distribute media that “advocates or promotes” terrorism, as well.

Guns in Canada

As a country with long traditions of hunting and trapping, Canada’s rate of gun ownership has historically been high, and Canada has some of the most liberal gun laws on earth. According to the Canadian National Firearms Association, there are presently about 21 million guns in Canada owned by about seven million Canadians — or about 20 per cent of the population — the majority of whom are recreational hunters. The most commonly owned guns in Canada are rifles and shotguns.

The Canadian government requires citizens to pass a safety course and undergo a background check before they can get a firearms Possession and Acquisition Licence (PAL) to legally own or buy arms, and laws governing gun storage and transportation are detailed and strict. Unlike most countries, Canada does not have national gun registry, though handgun owners must obtain a registration certificate to prove they are a legal owner. The government maintains a long list of banned guns, mostly semi-automatic rifles, though they can be rented for use in shooting ranges.

Gun control in Canada has proven to be an issue which sharply divides the country in terms of rural-versus-urban. For those who live in big cities, guns tend to be associated with inner-city crime, particularly gangland murders, and support to severely control or outright ban gun possession is usually high. Canadians who live in more rural parts of the country, in contrast, usually associate guns with hobbies like hunting, sport shooting and collecting, and see gun control as an undue burden that punishes the otherwise law-abiding.

Discrimination Protections

Canada has a fairly robust set of legal protections designed to prevent Canadians from being discriminated against on the basis of things they can’t control, such as race, gender, religion, or sexual orientation.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms is a section of the Canadian Constitution that makes it illegal for the government of Canada, or any provincial government to pass laws that either explicitly discriminate against certain Canadians on the basis of their identity, or simply place an unfair burden on one group over another. The Supreme Court of Canada routinely overturns laws they perceive to be discriminatory on the grounds of Charter protections.

Canada also has a sweeping piece of legislation called the Canadian Human Rights Act that forbids private entities, such as employers, landlords, schools, and stores from discriminating against clients or customers on the basis of identity. Discrimination cases of these sorts are investigated by the Canadian Human Rights Commission and adjudicated by a court-like body known as the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal that has the power to issue fines and or other corrective actions. The various provincial governments have their own human rights laws, commissions, and tribunals as well.

Cheering Montreal's 2013 Pride Parade.

Paul Vance/Shutterstock

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Rights

Canadians’ attitudes towards same-sex relationships have greatly liberalized over the last couple decades. Beginning in 1969, most legal bans on “sodomy” were lifted, and since then, more and more Canadians have been comfortable living “out” lives as open homosexuals. Provincial governments now explicitly prohibit discrimination in employment or housing on the basis of sexual orientation, and the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that it is constitutional to impose fines or bans on those who spread aggressively anti-gay “hate speech.” At the same time, homosexuality can still be an issue that makes some Canadians uncomfortable. Many gay or lesbians may experience tension with their families in the aftermath of “coming out” (particularly in more rural or religious parts of the country), and many same-sex couples may not be comfortable showing affection in public, with the exception of known “gay-friendly” venues or neighbourhoods.

After years of opposition from both major parties, in 2005 same-sex marriage was legalized in Canada when the short-lived government of Prime Minister Paul Martin (b. 1938) passed the Civil Marriage Act, which redefined marriage as simply a “lawful union of two persons.” The law was opposed, and continues to be opposed, by many Christian groups and political conservatives, but in 2016 the Conservative Party formally abandoned its promise to reverse the legislation.

Transgenderism, or being born into a biological sex that does not match one’s psychological gender identity has only very recently become a matter of mainstream attention in Canada, and it remains a topic that is far more controversial and contested than homosexuality. All provincial health plans recognize gender dysmorphia — the medical name for the state of being transgender — as a valid medical condition, and will cover the costs of sex reassignment surgery (also known as gender-confirming surgery). That said, there are almost no surgeons in Canada who actually perform the procedure, and many trans Canadians must travel abroad — and often pay out of pocket — to have it performed. Many Canadians may be hostile or skeptical of transgender people, though there is also growing acceptance of trans people as a legitimate minority deserving of public compassion and legal protection.

Prostitution

Selling sex is legal in Canada, but purchasing it is not, a somewhat confusing status quo born from a 2013 Supreme Court ruling holding that previous attempts to outlaw selling represented an undue burden on the safety rights of prostitutes.

Canada’s new prostitution laws, passed in 2014, impose tight regulations on precisely how sex can be sold and advertised — generally as far from public view as possible, and only by the prostitute herself (as opposed to a pimp, madam, or brothel).

Prostitution is incredibly stigmatized in Canada, and sex work is considered an incredibly dangerous and offensive job. Many Canadian prostitutes are poor women (and to a lesser extent, gay men) who come from some of society’s most marginalized groups, such as drug addicts, refugees, or aboriginal Canadians. Despite laws forbidding it, many prostitutes are likewise trapped in exploitive relationships with their managers that are both physically and economically abusive. In recent years, it has been more common to see charitable groups in large Canadian cities that actively work to improve the conditions of sex workers, though this has also faced controversy for “normalizing” prostitution.

Gambling in Canada

First legalized in 1969, government-run gambling underwent a dramatic boom in Canada during the 1980s and 1990s, largely as a way for provinces to increase their budget revenues without raising taxes. All provinces are now home to a wide variety of legal games of chance, including slot machines, casinos, sports bookies, animal racing, and video lottery terminals (or “VLTs”). In 2010, the province of British Columbia went even further and became the first jurisdiction in North America to legalize internet casinos as well. It should be noted that in all these cases gambling services are government-run; it remains illegal in Canada to run a private casino or betting house.

The provincial governments all run lottery corporations that sell so-called “scratch-and-win tickets” and other lottery tickets at corner stores and lottery kiosks in shopping malls. There are two national lotteries in Canada, the Lotto 649 and the Lotto Max, with winners picked every month. Winners are chosen from their ability to successfully predict a string of randomly-drawn numbers.

Compared to some of the other issues discussed in this chapter, gambling is generally only a minor controversy in modern Canada. While most Canadians may not want a casino in their neighbourhood and may be aware that there are health problems associated with too much gambling, casual gambling once in a while is a fairly common pastime unlikely to evoke much judgment from others. Buying lottery tickets has a relatively mild social stigma as stereotypically “lower class” behavior.

Death Penalty in Canada

From 1859 to 1962, the Canadian government executed 710 convicts, mostly by hanging, for various crimes involving murder or treason. After a series of controversial cases, a moratorium on further executions was imposed in 1967, followed by the outright abolishment of the death penalty in 1976, by the Liberal government of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau (1919-2000).

Despite being execution-free for more than 30 years, public support for executing murderers remains high in Canada, though no Canadian political party officially supports reversing the current ban.

Animal Rights

Though pet ownership (cats and dogs, mostly) is common in Canada, it’s not a right, and pet owners are often discriminated against in law. Many public buildings, including apartments, forbid animals and in many parts of the country the types and breeds of animals you’re allowed to own is limited by provincial law. The physical abuse of animals remains a crime, however.

Welfare and Pensions in Canada

In response to increasing Canadian life expectancy, the Canadian government has created various pension programs to ensure Canadians will still have access to a livable income even after they are too old to continue working. Today, every Canadian’s paycheque includes a deduction for the Canadian Pension Plan (CPP), which is then pooled by the federal government, partially invested in the stock market (via the CPP Investment Board), and then redistributed in the form of pension cheques to citizens over the age of 65. In addition, there is also the similar but optional Old Age Security Pension (OAS) program, which can be opted into by retirement age seniors who have lived in Canada for a significant period of time. Of course, this is just a broad summary. Both programs are, in fact, extremely complicated and bureaucratic, and likely to get even more so as the government is forced to deal with a rapidly aging population. About half of all Canadians are also part of a private pension plan through their employer.

- Public Pensions, Government of Canada

- Reality check: Is CPP going to be around when you retire?, Global News

Welfare is a broad term that basically refers to various forms of financial assistance that are paid by the government to people who, for whatever reason, are not working. Employment Insurance (formerly known by the more dour name Unemployment Insurance) is the most common form of this, and is available to Canadians who have been unexpectedly laid off or forced to quit their jobs for reasons such as pregnancy, illness or injury, or to take care of a sickly loved one. Most provinces offer similar programs known as income assistance for people unable to work, as well as disability assistance programs for people with limiting physical impairments.

In general, welfare programs are fairly controversial in Canada and there are social taboos associated with using them for too long. Since the 1990s, welfare rules have gotten steadily stricter, and now it’s usually expected that welfare recipients will be actively seeking jobs or otherwise making plans for their future while on it.