Arborg, Manitoba (Icelandic)

No

People of Canada

"... the Government of Canada recognizes the diversity of Canadians as regards race, national or ethnic origin, colour and religion as a fundamental characteristic of Canadian society..."

From the Canadian Multiculturalism Act (1985)

Who are Canadians?

Canadians didn’t just spring from the soil. Aside from a small community of aboriginals who migrated to North America more than a 12,000 years ago, everyone who lives in Canada is descended from relatively recent immigrants who left their native homelands to eke out a better living in North America.

About 80 per cent of Canadians are of European background — more commonly called caucasians or whites — with the remaining 20 per cent a diverse mix of literally every other race on Earth.

English-Canadians

Canadians of British descent, known as English-Canadians, Anglophones, or simply Anglos, have traditionally comprised the majority of people in all Canadian provinces and have a long history of trying to shape Canada’s national culture to mimic the customs, traditions, and politics of their historic motherland. This cultural dominance helps explain why Canada remained a colony of the British Empire for as long as it did, why it fought so eagerly for the British side in both world wars, why it took so long to take the Union Jack off the Canadian flag, and why institutions like the monarchy survive to this day. Anglo-Canadians have a lot of cultural similarities with Anglo-Americans in the United States as well, and today the U.S. exerts far more cultural influence over English-speaking Canada than Great Britain.

British immigrants came in waves; some Anglo-Canadian families have been living in Canada so long they have no idea when their forefathers first sailed over, some are the descendants of Loyalists who fled the American Revolution (1776-1783) while others may be the offspring of English or Scottish workers who left the British Isles during the 20th century. Motivated by a desire to keep Canada British, Canadian law favoured immigrants from the United Kingdom quite explicitly. Until 1976, there was no legal difference between a “Canadian Citizen” and a “British Subject,” meaning Brits were not subject to the same immigration regulations as other overseas migrants to Canada.

Quebecers celebrate Quebec's national holiday, Fête Nationale, on June 24, 2010.

Anirudh Koul/Flickr

French-Canadians

Co-existing (often uneasily) with Canada’s Anglos are the French Canadians, or Francophones, who represent the second-largest ethnic demographic in Canada — around 20 per cent of the national population. Concentrated mostly in the province of Quebec, French-Canadians are sometimes considered a unique North American race since the majority of French immigration to Canada ended after the French Empire was kicked out of North America in the late 18th century. Most French-Canadians thus trace their roots back to a very small community of inter-marrying colonial families from the 17th or 18th centuries, sometimes known as the Québécois de souche (roughly, “the original Quebeckers”), who survived mostly through high Catholic birthrates.

The survival of a large, unassimilated French-speaking community in a country as historically English as Canada is one of the world’s great demographic success stories, and is now often applauded — even by Anglos — as a vital component of Canada’s unique cultural identity. As a result, even small French Canadian communities outside of Quebec, such as the Franco-Ontarians, Franco-Manitobans, or Acadians (descendants of French settlers in the Maritime provinces) are now likely to enjoy explicit cultural protection and support from the federal government, since they help reinforce the idea of Canada as a country with a strong French presence.

Other European-Canadians

After French and English, the most common European backgrounds claimed by Canadians are Irish (13 per cent), German (10 per cent), and Italian (five per cent). Many Canadians of these groups are the descendants of poor immigrants who came to Canada in the late 19th century and worked as low-income sustenance farmers or factory workers before moving into comfortable middle class life in the 20th century.

Likewise, in the early 1900s, the Canadian prairies were settled by sizable amounts of immigrants from Eastern Europe (particularly Ukraine and Poland) and Scandinavia, who served as homesteader farmers in the new provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Many of these immigrants came from fundamentalist Christian sects, particularly the Doukhobors and Mennonites, and European-Canadians from these communities continue to play a prominent role in prairie culture to this day.

Today, Canada’s rate of immigration from Europe is quite low, and many Canadians of European background will mostly associate their European heritage with their parents or grandparents, as opposed to something that colours their day-to-day lives or culture. Over the course of several generations, Canadians from non-British or non-French European backgrounds have been generally assimilated into broader English or French Canadian culture, though some distinct “old world” traditions, habits, and beliefs may still be kept alive within families or community groups.

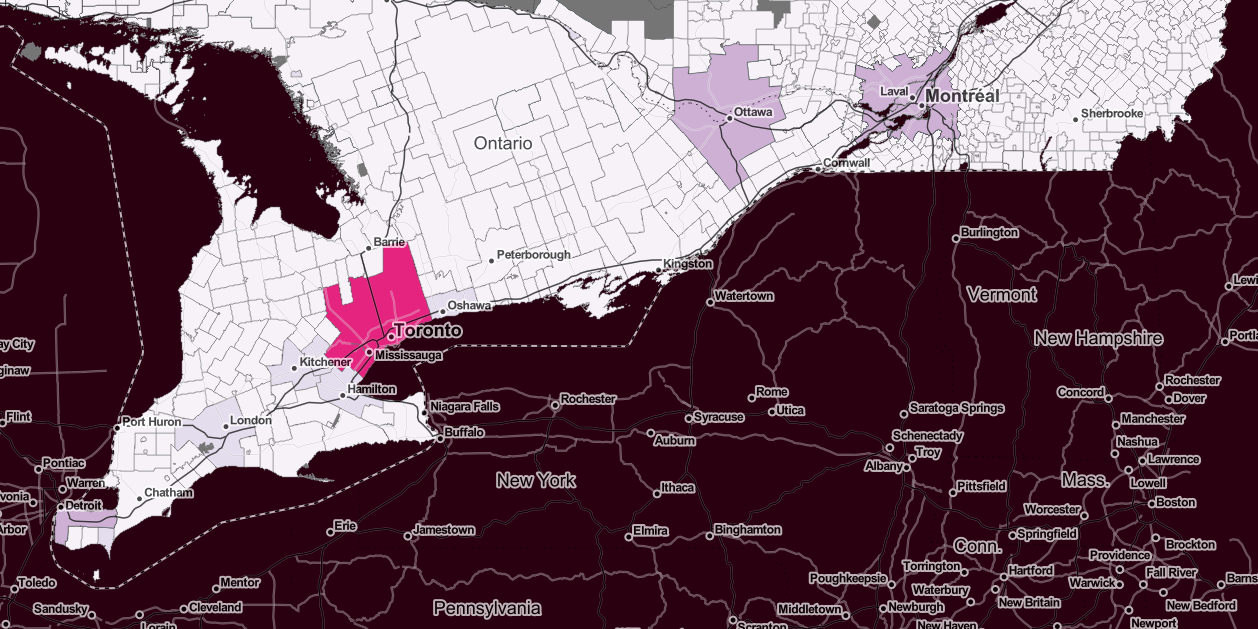

A colour-coded map of Ontario showing where racial minorities in Canada live in the highest numbers.

Visible Minorities in Canada

For much of its history, Canada was an overwhelmingly white country in which exclusionary and racist attitudes against non-white people and immigrants were very common. This changed in the aftermath of World War II (1931-1945), when the fall of Nazi Germany helped discredit theories of eugenics and a hierarchy of ethnicities, while the Civil Rights Movement in the United States provoked whites to adopt more tolerant attitudes toward visible minorities. Throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, changes were made to Canadian immigration law that eventually removed all racial and ethnic caps and quotas. These reforms ushered in a large inflow of new Canadians from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East in the last half of the 20th century, with immigration rates remaining high to this day. Canada now has more than five million non-white residents accounting for more than 20 per cent of the national population (or one in five Canadians), and upwards of 80 per cent of all new immigrants to the country are non-white as well.

Depending on what part of the country you visit, however, Canada’s racial diversity may not be particularly evident. According to Statistics Canada, 95 per cent of Canada’s visible minorities live exclusively in the country’s big cities, with six out of every 10 non-whites living in only two particular cities — Vancouver and Toronto. Rural Canada continues to remain largely white, though there is growing interest these days in ensuring immigrants settle more evenly across the country.

Though Canada is considered one of the most tolerant countries on earth, inequalities between whites and non-whites continue to exist, and many minorities claim they still encounter racism in their daily lives (see sidebar). In large Canadian cities, ethnic minorities and new immigrants are likely to be seen disproportionately working low-skill jobs like restaurant cooks, taxi drivers, janitors, or construction workers, but only rarely in executive or managerial positions. That said, Canada also has a very strong immigrant middle class, with Canadians of Chinese or East Indian heritage in particular (see below) often prominent small businessmen, doctors, real estate agents, bankers, or government bureaucrats — particularly within their own communities.

Asian-Canadians

After whites, Canada’s largest ethnic group are Asians, a term Canadians generally use to refer to people from the Pacific nations of China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines. Though bureaucrats and demographers sometimes use the term “Asian” to refer to people from the Indian Ocean region too, such as Indians, Pakistanis, Sri Lankans, and Bangladeshis, in day-to-day conversation most Canadians refer to these folks as Indo-Canadians, East Indians, or South Asians.

Both categories of Asians have been present in Canada for over a century. Imported Chinese labourers — who were specifically recruited for their willingness to work for low pay in dangerous conditions — were crucial to securing the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railroad, while some East Indians were able to overcome bigotry and establish themselves as successful merchants in British Columbia. Today, however, the vast majority of Asians and South Asians in Canada are either new immigrants or their children, the fruits of Canada’s aggressive intake of immigrants since the 1960s.

At around five per cent of the national population, South Asians remain Canada’s single largest minority group, followed by Chinese-Canadians at about four percent. The provinces of British Columbia and Ontario are known for having many large communities of both, and in some neighborhoods they may even comprise the majority of the population. Richmond, B.C. is the Canadian city with the largest Chinese population, while Brampton, Ontario houses Canada’s largest Indo-Canadian community.

Black Canadians

After Asians and East Indians, Blacks comprise Canada’s largest population of visible minorities, at around three per cent of the population. The vast majority of these come from recent immigrant families from either Africa or the Caribbean, but there remains a small minority of black Canadians whose roots trace back to the millions of African slaves imported to North America during the long era of the Atlantic Slave Trade (c. 1619-1807).

Slavery was less common in the Canadian colonies than the United States, though this was more due to economic factors than moral ones. During the 18th and early 19th centuries, the Canadian colonies, under both French and British rule, remained much poorer places than the southern American colonies that became the United States. Canadian farms were often small, and run by sustenance farmers who neither needed nor could afford the sort of large-scale slave labour common to big agricultural plantations. The African slaves that did exist in Canada were more commonly found working indoors in wealthier households as personal servants or so-called house slaves.

Canada’s relationship with people of African descent has always been complicated. On the one hand, the fact that the British Empire outlawed slavery in 1833, several decades before the United States, was often used as a symbol of anti-American pride, and Canadians enjoyed hearing stories of American slaves who were brought to freedom in Canada via the Underground Railroad – a covert human-smuggling network in the U.S. On the other hand, a lot of Canadians blamed Blacks for the social ills of America, and weren’t too keen to live alongside them. Early African-Americans settlers in Canada were often isolated in poor ghettos, such as the infamous Africville slum in Nova Scotia, and had to fight daily against bigotry and discrimination. Only very recently have there been aggressive efforts to recognize and celebrate the contribution of Blacks Canadians to the country’s history and culture – most prominently in 2017, when Viola Desmond (1914-1965), a Black Nova Scotia woman who unsuccessfully protested a segregated movie theatre, became the first person of colour to appear on Canadian currency. Today, most of Canada’s Blacks live in the cities of Toronto and Montreal with a culture that is heavily intertwined with that of African-Americans in the U.S., or the African or Caribbean countries in which many black Canadians were born.

Women in traditional Korean costume perform at a Canada Day celebration in Toronto.

DayOwl/Shutterstock

Canadian Immigration

The modern diversity of Canada is a reflection of Canada’s immigration laws, which are some of the most generous in the world. Beginning in the 1980s, Canada has been consistently welcoming a very high intake of immigrants in relation to the national population, usually approving over 250,000 immigrants as legal, permanent residents every year. In 2017, the number was over 286,000.

There are multiple reasons why the Canadian government has been eager to keep the country’s immigration rate so high. Immigrants are widely seen as helping contribute to the growth of the Canadian economy, particularly by filling various low-skilled or low-paying jobs native-born Canadians are not interested in. Many may also view welcoming immigrants as something Canada is morally obligated to do, given Canada is a free, safe country that has historically welcomed peoples from all over the world fleeing poverty or oppressive governments. Another consistent theme of Canadian history has been a dream of making the country larger in order to increase Canada’s wealth and power in the broader world.

People interested in immigrating to Canada can apply for various immigrant visas that allow them to legally live and work in Canada, and, in time, be eligible for long-term permanent residency and finally citizenship. The majority of immigrants to Canada come through dependents’ visas given to spouses or relatives of other immigrants. Most so-called “primary” immigrants (who are eligible to sponsor other immigrants) come through economic visas. There are various ways to qualify as one of these economic immigrants, such as by having a job offer or possessing skills in a field the government determines Canada to need. There are also visas for refugees fleeing war or violence in their home countries, visas for students studying at a Canadian school or university, and short-term visas for people visiting Canada for an extended vacation, work assignment, or working holiday, among others. Becoming a full citizen of Canada is eligible only to permanent residents who have completed a citizenship test proving they understand Canadian culture, language, and values.

Multiculturalism

As we’ve seen, Canadians from different ethnic backgrounds have not always found it easy to coexist. Tension, bigotry, and discrimination has been more common than not for much of Canadian history, which may help explain why so many Canadians celebrate the idea of peaceful multiculturalism today. What exactly “multiculturalism” means is hard to define, since not everyone uses the same definition. Broadly speaking, it refers to the idea that Canadians should respect and celebrate the diversity of their population. What that requires Canadians to do in practice, however, is subject of ongoing debate.

To some, multiculturalism means not imposing an undue burden on immigrants to assimilate to some idealized norm of “what a Canadian should be.” Under this logic, a Canadian bank might hire Chinese-speaking tellers, or a Canada Day festival might include Latin folk dancing. In both cases, the principle of inclusion reigns supreme. Others, however, might argue that multiculturalism means creating unity out of diversity, and encourage Canadians of all backgrounds to focus on uniting behind shared patriotic symbols or ideas like democracy, the flag, or Remembrance Day, and not over-emphasize their race, religion or heritage as things that keep them different from other Canadians.

- Canadian Multiculturalism, a definition from the Government of Canada

- The Canadian Multiculturalism Act (1985)

No matter how you define it, the project of building an effective multicultural society is not without its challenges. Today, Canada’s very large intake of immigration and the rapid pace at which this has transformed Canadian demography (as recently as 1981, Canada was close to 97 per cent white) continues to prompt discussion over what such population changes mean for the future of the Canadian identity, the unity of the country, and the rights of all Canadians. Many will argue that even as Canada’s media and government loudly celebrate diversity, old challenges of racism and racial inequality continue to be very present in the lives of Canada’s racial minorities. But just as many will confidently assert that Canada has handled the task of achieving domestic peace amid a highly diverse population better than many other nations.