No

Indigenous Peoples of Canada

The Indigenous people of Canada a small but influential community that remind Canadians of their country’s ancient past and their contemporary responsibilities to its first residents.

By most measures, Canada is a very young country, and Canadians are a very new people. The vast majority of Canada’s population is descended from European immigrants who only arrived in the 18th century or later, and even the most “historic” Canadian cities are rarely more than 200 years old.

But thousands of years before any Europeans arrived there were still people living in Canada. Canadian Aboriginals, also known as Native Canadians, the First Nations of Canada, Indigenous Canadians, or Canadian Indians, are the modern-day descendants of the first human inhabitants of North America.

History of Canada’s First Peoples

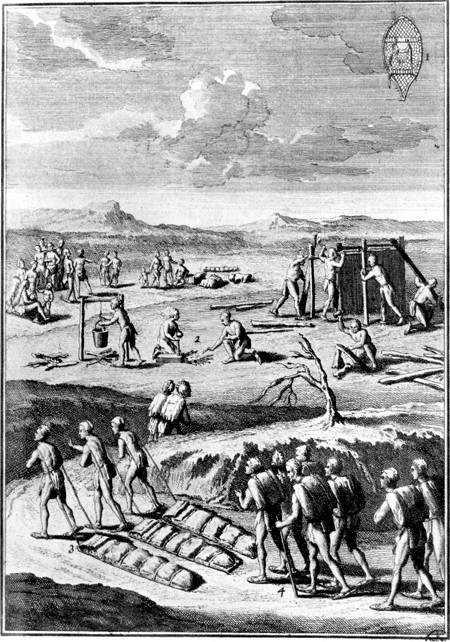

Everyone has to come from somewhere, and most archaeologists believe the first peoples of Canada, who belong to what is sometimes called the Amerindian race, migrated to western North America from east Asia sometime between 21,000 and 10,000 B.C. (approximately 23,000 to 12,000 years ago), back when the two continents were connected by a massive land bridge known as the Bering Plain. In the centuries that followed, these peoples spread all across the lands that now comprise Canada and the United States, forming hundreds of distinct communities across the vast landscape. Though population estimates vary wildly, the early Amerindians surely numbered in the millions.

The Pre-contact Nations

The Aboriginal peoples of Canada are divided into around historic 50 nations or tribes, which are groups defined by bloodline and culture, which are then split into more than 600 smaller bands, which are more of a political community. Overall, Canada’s Native peoples can be sorted into six broad groups, defined mostly by where in the country they have traditionally lived:

- The Haudenosaunee, also known as the people of the Eastern Woodlands, are Canada’s largest Native community, and historically lived in farms around the St. Lawrence river and Great Lakes in modern day Ontario and Quebec. Famous for their distinctive long houses, they were organized into a powerful political coalition known as the Iroquois Confederacy, and were the first to make substantial contact with European explorers. Notable nations include the Algonquin, Huron, Mohawk, Mi’kmaq, Ojibwa, and Ottawa.

- The Great Plains or Prairie people lived in the territory that today forms the Prairie provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Their livelihood came from hunting the wild buffalo of the region, and they famously used “every part” for survival. As western North America was settled by Canadians and Americans in the 19th century there was much conflict between these white pioneers and the Plains Indians, with these stories then heavily glamorized by Hollywood and others. As a result, Native traditions from this part of the country, such as feathered headdresses, tepees and tomahawks are probably the most internationally well-known and stereotypical. Nations include the Blackfoot, Cree, Ojibwa, and Sioux.

- The Native peoples of the Northwest Coast lived along Canada’s Pacific coast, in modern-day British Columbia. They were primarily fishermen who lived in houses dotted along the beach, and are today best known for their distinctive artwork, including wood carvings and totem poles. Northwest Coast Indians divided themselves into very a large number of very small communities, with the most prominent nations being the Haida, Nootka, and Salishan.

- The Plateau people were a small but distinctive Native community who lived in an elevated area in southeastern British Columbia between the Rocky and Cascade mountain ranges. Athapascan, Ktunaxa, and Interior Salish are their primary nations.

- The Subarctic people were nomads who lived all across the barren, northwestern half of Canada in temporary, movable shelters. They hunted the caribou and followed its migration pattern. Given the vastness of the territory they occupied, which spanned from the island of Newfoundland to Yukon, the Subarctic people contained a large number of nations, many of which overlapped with the nations of other regions, including the Algonquin, Athapaskan, Beaver, Cree, Dene, and Slave.

The Inuit

The Inuit people of the Arctic, also known by the now-offensive name “Eskimo“, lived in the Canadian arctic, some of the most inhospitable terrain in the entire world. They hunted seals and caribou and lived in distinctive snow houses called igloos. The Inuit were North America’s last major aboriginal community to make contact with whites, and did not begin to substantially modify their ancient lifestyles until just a few decades ago. Inuit are not usually divided into “nations” the way other aboriginal peoples of the continent are, but are rather treated as a completely unique Indigenous people, separate and distinct from other Amerindians.

Despite their differences, most aboriginal nations shared certain common characteristics, particularly hunter-gatherer sustenance lifestyles, deep respect for nature, egalitarian and communal social values, and deep and detailed spiritual beliefs. Many had permanent housing, farms, and stable political structures, as well as rich cultures with distinctive traditions in art, fashion, song, and dance. At the same time, most Native communities also lacked a written language, used only simple weapons, and had mostly superstitious understandings of basic scientific concepts. Differences between the sort of knowledge and lifestyles aboriginal people valued and the knowledge and lifestyles valued by non-Indigenous people has long been a source of intense, and often tragic racial conflict in Canada.

Contact With the White Man

When Europeans first arrived in eastern North America in the mid-1500s, most regarded the continent’s Indigenous residents as a hopelessly backwards people greatly inferior to themselves. Missionaries were dispatched to convert this supposedly “godless” race to Christianity, while early French and British colonists saw them as a useful and easily-exploited source of cheap labour for the fur trade, soldiers for the battlefield, or even household slaves. As the European powers sought to colonize more of North America, violence or threats of violence were often used to drive Indigenous people from their homes or force their leaders to sign lopsided treaties that surrendered political control of their lands in exchange for meagre financial compensation or dubious promises of protection and safety.

In the end, however, it was disease that effectively weakened the Aboriginals beyond recovery. Unexpectedly exposed to dozens of new European illnesses for which they had no immunity or cure, millions of Natives perished from plagues of smallpox, Typhoid, and influenza. Some estimate that by the close of the 19th century, Canada’s Aboriginal population had declined by more than 90 per cent, with centuries-old Indigenous cultures all but extinguished by waves of European settlers.

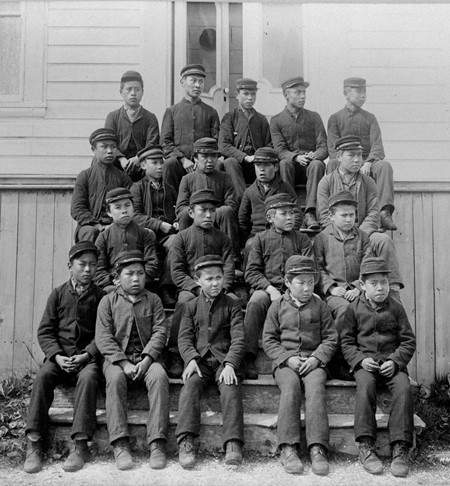

The late 19th century saw the Canadian government colonize the vast western half of northern North America with waves of white settlers, and in order to make space for them, Indigenous nations from this region were cajoled into signing yet more land surrender treaties. This era also saw the reserve system (see below) pursued with renewed vigour, with the goal of bringing the “Indian problem” to a close once and for all. Aboriginal communities were assigned to live and govern themselves in isolated, economically unimportant corners of the country, while heavy-handed assimilation initiatives like residential schools (see sidebar) attempted to eliminate Indian culture altogether. With the Native minority safely out of sight and out of mind, Canada’s new white majority found it easy to spend the next century largely ignoring Aboriginal concerns. Only very recently have attitudes begun to change.

"I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that this country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone… our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed Into the body politic and there is no Indian question and no Indian Department."

Duncan Campbell Scott, deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs (1920)

Dancers at an Aboriginal cultural festival held on a Mohawk nation reserve in Kahnawake, Quebec.

Alina R/Shutterstock

Indigenous Canadians Today

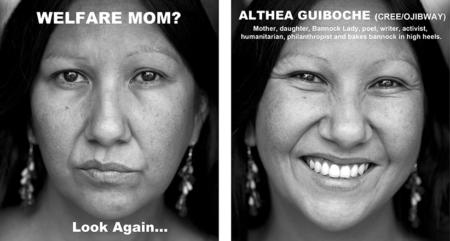

Today, Canada is home to about 1.7 million citizens who claim to be of Aboriginal descent (or about four per cent of the total population), the majority of whom identify as members of specific tribal communities, or First Nations, that have existed for centuries. About half a million Canadians identify as mixed-race Métis people (see above) while only about 65,000 consider themselves Inuit.

Aboriginal people are relatively evenly spread across Canada, though they are most concentrated in the prairie provinces of Manitoba and Saskatchewan, where First Nations and Métis people comprise more than 15 per cent of the population. The small northern territories of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories are the only parts of Canada where Aboriginal people (in this case, Inuit) outnumber whites, though these territories have less than 83,000 people in all. Most Canadian Aboriginals speak English as their first language, though there have been persistent efforts to preserve traditional Aboriginal languages, with Cree and Inuktitut remaining the best known and most widely spoken.

In many ways, Indigenous Canadians are little different from any other type of Canadian. They work, raise families, vote in elections, and otherwise participate as full members of Canadian society. In other ways, however, their lives are quite different, due to the continued existence of Aboriginal treaties and Indian reserves, which place Indigenous Canadians under a unique system of laws, controls, and benefits that are exclusive, distinctive, complicated, and — more often than not — deeply controversial.

Treaties and Indian Status

In 1763, Britain’s King George III (1738-1820) issued a Royal Proclamation in which Britain (and later Canada) vowed to only occupy lands in North America that had been “ceded to, or purchased” from the Indian nations. Many such agreements were in turn signed, with the Crown (that is, government) promising to offer Indigenous people services such as military protection, food, medicine, regular financial payments, special hunting and fishing rights, and a small area to use for housing in exchange for surrendering most of their land to white settlers.

These colonial-era agreements are still being honored today by the Canadian federal government, and the Constitution of Canada recognizes Aboriginal treaties as having the force of constitutional law. Any Aboriginal person who confirms their Native identity with their band government and the government of Canada is declared to be a “Status Indian” entitled to receive treaty promises. Many of these benefits require living on an Aboriginal reserve (see below). This is all governed by a complex and controversial piece of legislation known as the Indian Act, passed in 1876.

While most status Indians in Canada are covered by some sort of treaty, many are not, particularly in British Columbia and Quebec. Starting in the 1970s, the Canadian government began negotiating modern treaties with historically ignored Aboriginal nations through what is now called the land-claim settlements process. Such settlements have proved extraordinarily difficult to hammer out, however, routinely taking many years and involving enormous teams of lawyers and bureaucrats. Only a handful have been successfully negotiated, usually involving quite small communities.

Prime Minister Trudeau meets with the File Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council, which governs 10 First Nations in Quebec.

The Reserve System

A Indian reserve (or reservation) is a legally-protected area of land, defined by a treaty, where Aboriginal Canadians belonging to a particular nation can live in a state of semi-exemption from a number of federal and provincial laws, and participate in a self-governing society organized according to Native traditions. In practice, most reserves are small, isolated communities in very rural parts of Canada. They may resemble anything from a trailer park to a small village, and rarely have populations larger than a few hundred. Governance of the reserve is entrusted to an elected chief and band council, which may also be part of a larger tribal or national government. Most reserves still receive some sort of regular treaty payment from the federal government, and this money is used by the band council to provide residents with basic services such as housing, education, roads, police, and — in many cases — income.

Living “on reserve” exempts Native people from having to pay federal or provincial taxes, and, in most cases, entitles them to special grants to help pay for health care, post-secondary education, public transportation, and other social services. Aboriginal hunters and fishermen are likewise usually exempt from size and quantity restrictions, and if a reserve’s territory is lucky enough to contain natural resources such as oil or minerals, then the residents may be eligible to earn a cut of the royalties, too. These days, some Native bands have taken to exploiting the legal exemptions of their reserves to operate tax-exempt malls or casinos that make a lot of money for the tribe, as well as selling untaxed cigarettes or dubious products like fireworks, which may be banned by the surrounding city or province.

The Métis

The Métis (may-tee) are a distinctive group of people that exist in a unique place when it comes to Canadian law and culture regarding Native peoples. They are considered Indigenous peoples under Canadian law, but unlike other aboriginal Canadians, they do not claim to be the descendants of the first peoples of North America, but rather a unique racial-cultural community that only arose after Europeans arrived.

Métis people were originally understood to be the mixed-race descendants of Plains Indians and white settlers — mostly French Canadians — who formed a distinct subculture within the Canadian prairies from the 18th century on. Many spoke French, or a pidgin version of French known as Michif, and had traditions of dress, cuisine, and religion that was a sort of hybrid of Native and French Canadian culture. These days, however, more and more white Canadians with at least one Indigenous relative in their family tree have started self-identifying as Métis, provoking both a substantial growth of the community (and Indigenous identity in Canada more broadly), but also controversy among those who believe the term should only be used to describe descendants of a very specific mixed-race community in the prairies.

Though there is no national law for determining whether someone is or isn’t a “real” Métis person, court rulings in recent years have generally argued that governments should defer to the judgment of local Métis organizations in the provinces, for example, the Métis Nation of Ontario, or the Manitoba Métis Federation. Some Métis Canadians may partake in customs and traditions that seek to connect them to the Métis people in Canada’s past, others may see their Métis identity as something more personal and private, and mostly a reflection of family heritage. In 2023, the government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (b. 1971) passed legislation with the intent of negotiating future self-government treaties with Métis governments across Canada, akin to treaties already in force with other Indigenous nations.

Troubles

One of the great shames and tragedies of modern Canada is how poor the quality of life remains for Canadian aboriginals, even after several decades of aggressive government efforts to redress the sins of the past. Despite a multitude of targeted government programs and benefits, the life of a typical aboriginal in 21st century Canada remains significantly worse than that of any other racial group, with rates of poverty, crime, substance abuse, and domestic violence grossly disproportionate to their percentage of the population. Statistics show an aboriginal Canadian is almost 10 times more likely than a non-aboriginal to wind up in prison, and aboriginal youths have a vastly higher suicide rate than their non-Native peers.

The root causes of these social ills are numerous and complicated, but there are a number of popular targets. Historic racism is obviously a leading one, with the notoriously dysfunctional and abusive residential schools system in particular now often blamed for saddling multiple generations of Aboriginal people with broken families and deep social pathologies. The modern-day reserve system itself has many critics as well, given many reserves lack the quality of housing, employment, education, medical care, and even basic amenities like clean water and electricity other Canadians take for granted. Blame is either directed at an indifferent federal government (that fails to provide adequate funding to bands), or corrupt and incompetent band councils (who squander and misspend what funding they do get) — or both.

Others have argued that Canada’s entire system of dealing with Aboriginals is hopelessly backwards and colonialist. By continuing to revolve Aboriginal life around treaties and the Indian Act, which place so much responsibility on the Canadian government to finance, regulate, and supervise Aboriginal affairs, such critics say Canada’s Natives are kept in a perpetual state of dependence, unable to do much of anything without government support and consent. Many Canadian politicians and Aboriginal leaders thus support greater self-government powers for First Nations, which is to say, the ability for Aboriginal bands to independently pass their own laws equal in power to laws passed by the federal or provincial governments. This is a very dramatic idea that can conflict with the Canadian Constitution, however, so progress is often slow. A lot of efforts to redress the problems of Indigenous life in Canada now take the form of lawsuits that seek supportive rulings from the Supreme Court of Canada that would expand or clarify the powers of Aboriginal governments.

The one thing everyone seems to agree on, however, is that greater economic self-sufficiency for Aboriginal people is critically important to improving their quality of life. This is part of the reason why many Canadian Native bands are now working so hard to secure royalties from natural resources like oil or gas harvested from their traditional lands, or get a cut of profits earned by corporations operating pipelines, mines, dams, or fisheries within their band’s borders. Natural resource extraction remains the single largest employer of Aboriginal people in Canada.