No

The Economy of Canada

Canada is one of the world’s richest nations, with a highly sophisticated economy and a top-tier standard of living. Though obviously not everyone in Canada is equally well-off, most Canadians nevertheless hold reasonably well-paying jobs and access to ample creature comforts that citizens in many other countries can only dream of.

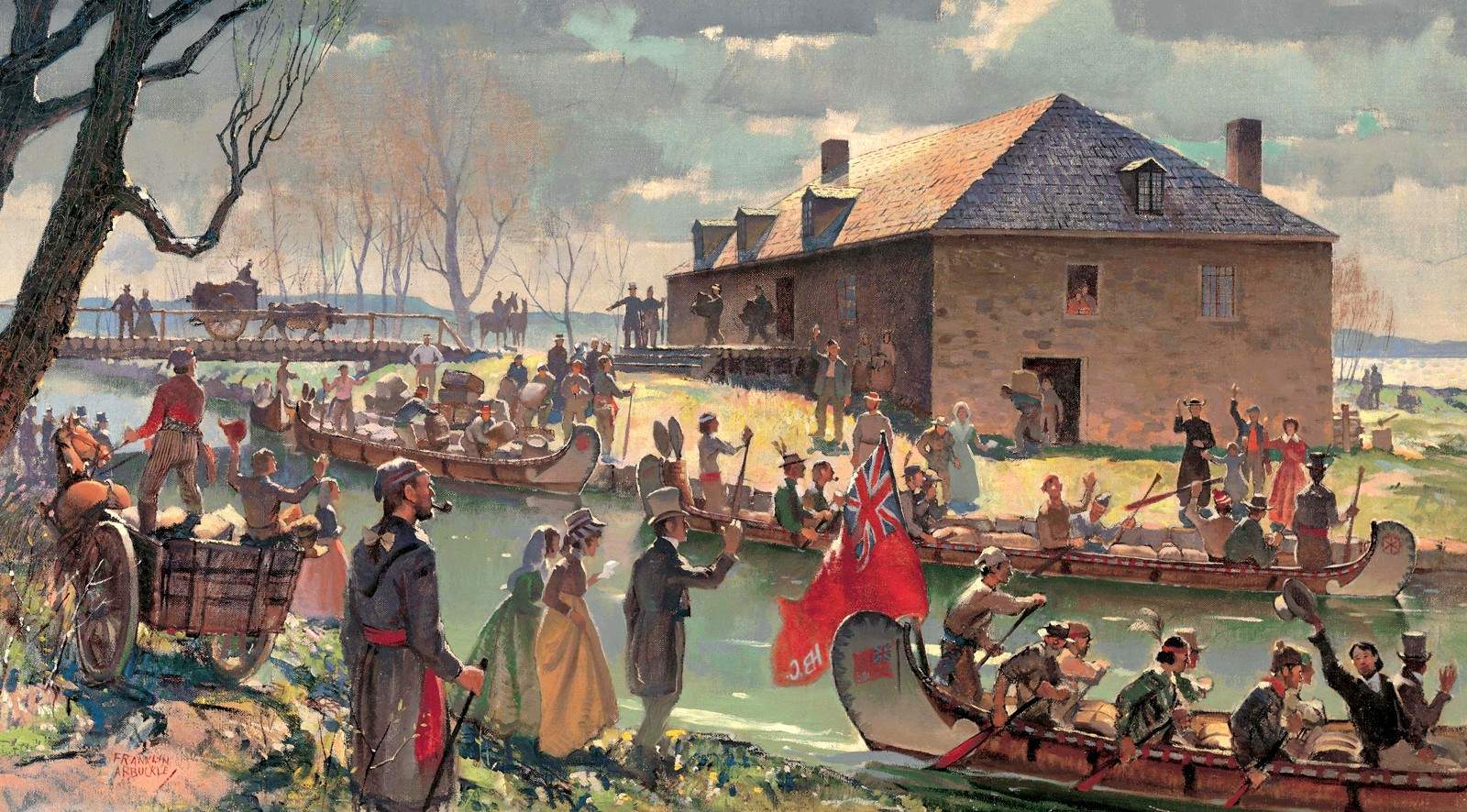

A romanticized image of 19th century fur traders rolling into town.

Franklin Arbuckle (1909-2001), HCB Archives

Economic History of Canada

Canada was basically founded as a money-making scheme. In the 17th century, when North America was first being colonized by the French and British, the northern half of the continent was considered an alluring place because of all the furry woodland creatures it contained, since beautiful, glossy furs were one of the most desired possessions of wealthy Europeans of the time. For centuries, the early Canadian colonies thrived under a simple economic system known as the fur trade, where hunters gathered and sold animal skins under the employment of large fur corporations — mostly the Hudson’s Bay Company — who then used their profits to purchase land and build trading posts in new areas where even more fur could be found.

As European settlers moved west from the St. Lawerence River region, they discovered Canada was full of lots of other things they could harvest and sell too, including lumber, fish, coal, iron, gold, and silver, which helped spawn powerful fishing, timber, and mining industries. The development of farms in arable regions, meanwhile, yielded ample harvests of wheat and other grains as well as meat and dairy products from raising livestock. Originally, much of Canada’s resource bounty was sold to Britain and France, the colonial rulers. But as the years went on, it soon became more logical and profitable for Canada to do most of its trade with the United States — which was considerably closer — or simply among cities and provinces within Canada itself.

The industrial revolution of the late 19th and early 20th centuries introduced all sorts of exciting new machines to the world, and saw Canadians begin to develop a robust manufacturing sector, with giant factories able to transform raw natural resources into useful high-tech things like paper, cloth, steel, chemicals, and automobiles, while dams and derricks enabled the production of new commodities like hydroelectricity, oil, and natural gas. In the decades following World War II (1939-1945), the Canadian economy shifted dramatically once again as industrial profits were invested into higher wages and taxes, and social services. A growth of schools, particularly affordable colleges and universities, produced a more educated population able to pursue office work and largely abandon manual labour in factories and farms, while Canadian corporations sought larger profits by outsourcing manufacturing jobs to cheaper workers in poorer countries. By the dawn of the 21st century, Canada had become an integrated part of a thoroughly globalized economy in which Canadian workers now only produce goods and services that cannot be produced cheaper in some other country. This has made life more affordable for many Canadians, but has come at the cost of eliminating many traditional sources of Canadian employment.

Canada’s Modern Economy and Industries

Having largely abandoned the country’s agricultural-manufacturing past, today upwards of 75 per cent of Canadians work in what is dubbed the service sector of the economy, while only a small minority still work in farms or factories. The service sector of the Canadian economy is extremely vast and diverse, and basically entails any sort of (mostly) non-physical work that deals with helping people, rather than making or growing things. Most Canadians who live in large cities like Toronto, Vancouver, or Montreal work in the service sector.

Within the service sector, the largest sub-sector is the trades, which are highly specialized, skill-based professions like electrician, carpenter, or computer repairman. Other large sub-sectors include health care, which includes doctors, nurses and surgeons, plus their clerks and assistants; finance, which includes bankers, stock brokers, and real-estate agents; education, which includes teachers, professors, librarians and administrators; and food and retail, which covers cooks, store clerks, and cashiers in places like shopping malls, restaurants, grocery stores, and other shops. Writers, artists, journalists, and entertainers, like actors or musicians, are all considered service workers, too. Government or bureaucratic work has also become quite popular in recent decades, with the Canadian federal government now said to be the single largest employer in the country.

Canada’s few remaining farmers reside primarily in the Prairie provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, where they continue to grow crops such as wheat, corn, and oilseed, as well as raise cattle and pigs for meat and dairy, just like their forefathers before them. In many parts of the country, a renewed interest in organic food is helping provide some Canadian farmers, particularly fruit and vegetable farmers, with a mini boom, but overall, Canadian agriculture remains very much an industry in decline.

Canadian manufacturing remains only slightly more lucrative, and still employs about two million workers, or about 13 per cent of the country’s total labour force. Like agriculture, it’s another industry highly concentrated in one part of the country, in this case the so-called “central Canadian region” of Ontario and Quebec, which together house more than 75 per cent of all Canadian manufacturing jobs. The most famous of these remain centred around Canada’s automotive sector, historically one of the leading symbols of Canada’s postwar economic boom, but now in steady decline as outsourcing and robotics lower the need for Canadian workers in this sector. In forest-rich British Columbia, the production of lumber and paper still dominates provincial manufacturing, while the production of food, chemicals, electronics, and other miscellaneous bits of machinery dominate in small communities elsewhere. As is the case with most western nations, much of what Canadians still manufacture in their own country consists of specialty products that are either too expensive or impractical to build overseas.

Shoppers pondering purchases at a Costco warehouse store in Hamilton, Ontario.

Alastair Wallace/Shutterstock

Trade and the United States

Trade comprises more than 65 per cent of Canada’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), making it one of the most trade-dependent countries in the world. Of this, upwards of 75 per cent of all Canadian trade is done exclusively with the United States, meaning the modern Canadian economy is extremely dependent upon, and integrated with, the economic happenings of America. So much so, in fact, that some economic analysts don’t think it’s even worth talking about “Canada” and the “United States” as two separate economic entities, so conjoined are their economies.

The most valuable goods Canada exports, or sells, to the United States are energy resources, namely oil, chemical fuels, electricity, and natural gas (many are surprised to learn that Canada, and not some country in the Middle East, is America’s biggest foreign source of oil). Raw natural resources, such as aluminum, nickel, gold, and iron ore are popular exports, too. Most of Canada’s remaining exports to the U.S. are simply half-assembled products that are then completed in America. Half-assembled cars comprise a particularly large category, and Canada and the United States jointly operate the largest automobile manufacturing sector on Earth, based out of the Ontario-Michigan border region. From the U.S., Canada imports just about everything, including food, finished cars, chemicals, electronics, and tons of entertainment products like books, movies, and video games. Overall, Canada is the single biggest foreign consumer of American goods and the United States runs a large trade surplus with Canada — meaning Canadians buy a lot more from the United States than the United States buys from Canada.

- Profile of Canadian trade, Observatory of Economic Complexity

- Canadian imports by product, Statistics Canada

- Canadian exports by product, Statistics Canada

Along with being the country’s biggest trade partner, the United States is also the single largest foreign investor in the Canadian economy, with around 50 per cent of all foreign direct investment in Canada held by Americans. Much of this investment takes the form of American corporations setting up shop in Canada. Cruise the streets of any major Canadian city and you’ll be greeted with an endless array of popular American chains, from McDonald’s to Starbucks to Wal-Mart, catering to Canadian customers. It’s not an entirely uncontroversial state of affairs; while American corporations provide millions of jobs for Canadians, critics argue the dominance of American companies in Canada hurts Canadian corporations and investors who have difficulty competing with Americans. The Canadian government does have rules that limit foreign ownership in certain industries deemed too important to trust to Americans (or any other foreigners, for that matter), including telecommunications, energy, national defence, and culture.

In addition to the United States, Canada currently has free trade agreements with much of Latin America (Mexico, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Honduras, Panama, and Peru), middle eastern allies Israel and Jordan, and the four non-EU countries in Europe – Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland, though the amount of trade Canada does with these countries is quite small. Canada’s second-biggest trade partners after the United States are the European Union, China, and Mexico, who collectively represent about 20% of all Canadian trade.

Taxes in Canada

Canadians like to complain about taxes, but compared to other major industrialized democracies, Canada’s rate of taxation is comparatively low. Total tax revenue in Canada represents about 32 per cent of the country’s GDP, compared to 36 per cent in Germany, 45 per cent in France and 47 per cent in Denmark. The bulk of the money Canadians give to their government is withdrawn through taxes on incomes and purchases, which are charged at both the national and provincial level.

Personal income taxes in Canada are progressive, which is to say, people pay a different rate depending on how much income they make. Federally, the bottom rate is 15 per cent and the top rate is 33 per cent, while at the provincial level most rates are (very roughly) half that. Corporations pay income tax too. The federal corporate income tax rate is a flat 15% (10% for “small businesses”), one of the lowest rates in the world, while the provincial rates are, again, roughly half that. The bulk of income taxes Canadians pay are deducted automatically from their paycheques, along with other specialized taxes that are used to finance the Canadian Pension Plan (CPP), unemployment insurance, and in some provinces, other services as well (these are known as payroll taxes). Canadians are expected to double-check their income tax records at the end of every fiscal year (April) and pay the government any outstanding income tax owed. Collection of provincial and federal income taxes is jointly managed by the Canadian Revenue Agency (CRA), meaning all tax related matters in Canada are handled by a single federal bureaucracy.

- Federal and Provincial personal Income Tax Rates in Canada, Canada Revenue Service

- Corporate Income Tax Rates in Canada, Canada Revenue Service

Everything you buy in Canada receives an extra mark-up at the cash register in the form of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and a Provincial Sales Tax (PST). These days, a lot of provinces merge the two taxes together to make things easier, in the form of a Harmonized Sales Tax, or HST. The GST rate is currently set at 5 per cent of purchase price, while PST rates vary from province to province, but is usually a bit higher.

Canadian Unions

In the old days, when Canada’s manufacturing sector was considerably larger and more important than it is today, many Canadian factory workers formed trade unions in order to lobby for safer working conditions and higher pay from their employers. As manufacturing declined, unionization steadily shifted towards white collar work, and of the 30 per cent of Canadians who hold union membership today, the majority work in fields such as teaching, nursing, or government bureaucracy.

In a reflection of this growing dominance of government employees in the Canadian labour movement, the largest union in Canada is now the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), which represents more than 615,000 Canadians working for the provincial and federal governments. Considerably smaller, the country’s largest private sector union is Unifor, which was founded in 2013 through a merger of various manufacturing unions. It represents over 300,000 workers. Most union workers are also members of labour federations in their provinces, and there is a national lobby group for union interests known as the Canadian Labour Congress.

Canada is not a country that experiences a great deal of labour unrest, and strikes are usually short and rare. Since an increasing number of the country’s unionized workers now perform safe, comfortable jobs for government employers, contract negations have lost a lot of their earlier passion and intensity, and are now mostly around the calm negotiation of things such as vacation lengths, sick days, and layoff procedures. Workers in certain professions the government deems “essential services,” such as police, hospital workers, and firefighters are not legally allowed to strike.